by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Atmospheric Art.

Wish for Film Set Wallpaper.

Eccentric Orbits.

Fig. It. Out.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Atmospheric Art.

Wish for Film Set Wallpaper.

Eccentric Orbits.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

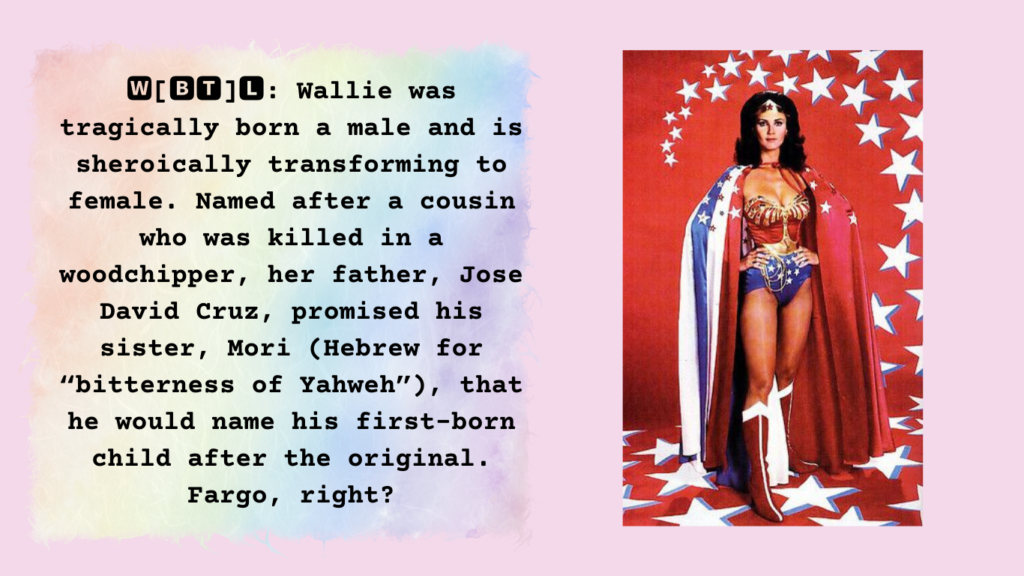

Graphic Design by Wallie Cruz

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

“Sometimes the Dreamers . . .”

Past Lives, In-Yun One More Time.

. . . Finally Wake Up.”

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Rivets and Divots.

All Parents Are Dangerous.

Inside Jokes Bespoke.

Postscript: MacGuinness and I spotted tall Cousin Greg w/friends one night at Saint Anne’s.

R.I.P.

PDQ Review: Igby Goes Down

Are Igby’s highfalutin family and foes just a figment of his imagination? It’s kind of like a boho version of the ‘Island of Lost Toys.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Beauty Marks the Spot.

Upstairs Downstairs Below Deck.

Fish For Compliments.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Daze in The Valley.

Emily the Criminal.

It’s a Hard Knock Life.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

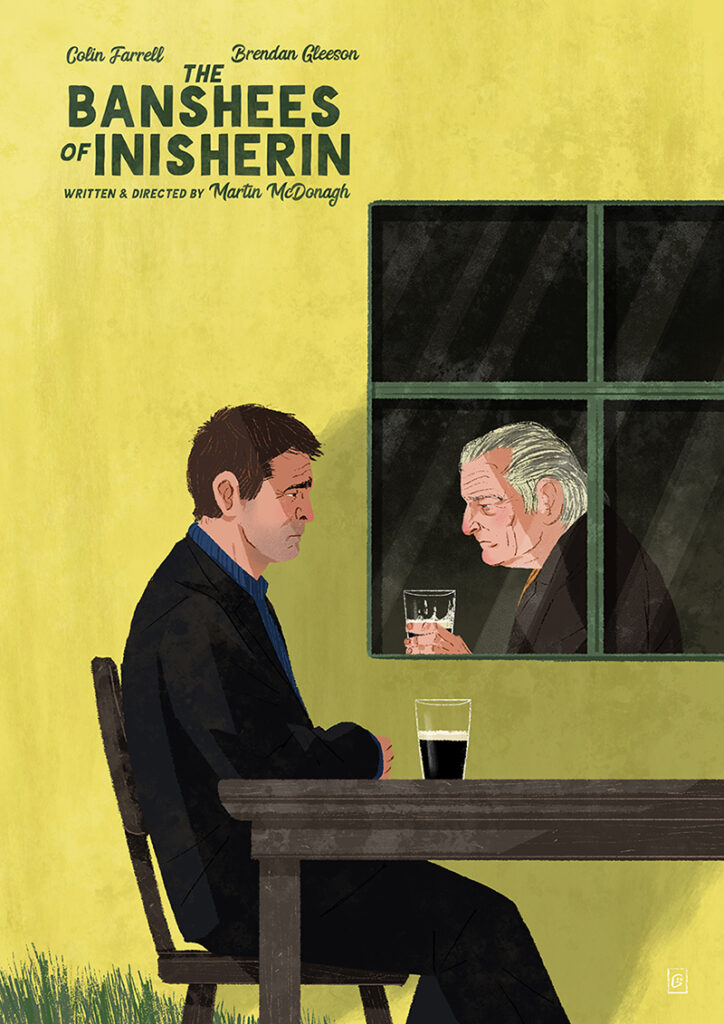

What the feck?

by Kerrin Ross Monahan

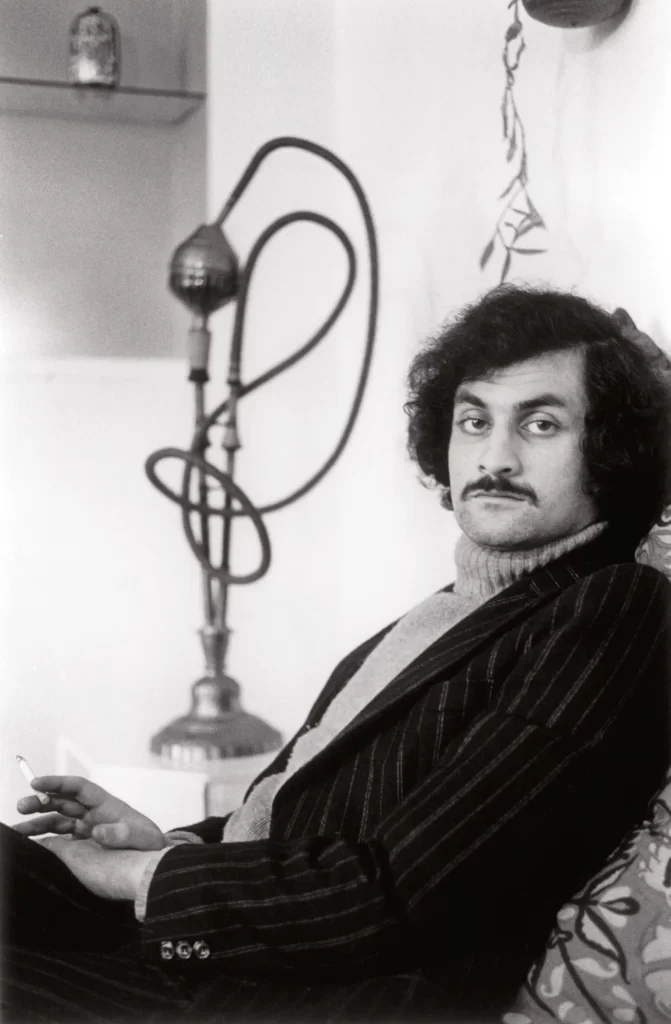

| “Words are the only victors.”—Salman Rushdie’s Victory City Salman Rushdie is a brilliant, inventive, and most important of all, an acutely perceptive writer. He won the 1981 Booker Prize for Midnight’s Children, and in 1988, with the publication of The Satanic Verses, unleashed the fury of Islamic zealots, causing him to go into hiding for fear of being assassinated, due to a fatwa issued against him by the Ayatollah Khomeini. In 1990 he wrote the vastly humorous and magical Haroun and The Sea of Stories. In 1995, he received the Whitbread award for The Moor’s Last Sigh. In 1998 he wrote The Ground Beneath Her Feet, and the author issued a collection of non-fiction (1992-2002) Step Across This Line, in which he shows us that he will not let the fatwa define him; he will define it. Rushdie’s writings demonstrate themes of opposites: comedy and drama, life and death, light and dark, good and evil, angels and devils, and, in Shame, up (hell) down (heaven), as well as shame and shamelessness. He draws on a vast knowledge of Eastern and Western history, literature and culture. The tone of his work also shows opposites: fireworks here, a steady flame there; shooting stars, then an unwavering glow. Rushdie is a good genie, who holds up his lamp and illuminates the whole world in order to expose the religious, political, and national evils that exist where societies remain closed. He is a great crusader who has given up a large part of his own personal freedom in order that others may keep theirs. (Perhaps some day, the pen will prove mightier than the sword.) But the author knows that good and evil are so often tightly entwined. In Midnight’s Children (the story of modern India, but can also be applied to the emergence of the evil and destructive component of the modern Arab world as a whole), he laments: “. . . it is the privilege and the curse of midnight’s children to be both masters and victims of their times, to forsake privacy and be sucked into the annihilating whirlpool of the multitudes, and to be unable to live or die in peace.” It can indeed be said that we are all midnight’s children to a degree—caught between good and evil, life and death. Let us pray to Yahweh, Jehovah, Abraham, Jesus, God, Mohammed, and Allah, that we will all be able to live and die in peace. Pax Vobiscum. “In the name of God, the compassionate, the merciful say: I seek refuge in the Lord of men, the King of men, 114:1. The God of Men, from the mischief of the slinking prompter Who whispers in the hearts of men; from jinn and men” 114:6 (The Qumran). Shame was written in 1983 and can be considered purposefully prophetic today. The Washington Post “Book World” commented back then on Rushdie’s ” . . . ability to convey, to a Western readership, the physical and psychic landscapes of (the East).” In Salman Rushdie’s Shame, Omar Khayyam Shakil, the most important character in the book, is never really at center stage until the very end of the story. Omar considered himself a “peripheral man . . . born and raised in the condition of being out of things” (p.10). Not only did he feel that he was living at the edge of the world, he also perceived that he had grown up between “twin eternities” (p.17) existing in a kind of limbo between Heaven and Hell. He had an inverted sense of things from the moment of his birth, when, hanging upside down, his first vision was of the “inverted summits” that he later named the “Impossible Mountains” (p.14). Rushdie plays upon these themes of periphery, limbo, and inversions all through the book, and time and again invests everything with political and religious overtones. The central theme is shame and shamelessness, their evil and violence and how they manifest themselves in all of the characters, especially Omar, and ultimately their consequences. Omar was named after the famous Eleventh Century Persian poet, Omar Khayyam. Not only was he noted for his immortal Rubaiyat (“Quatrains”), a thousand epigrammatic fourth line stanzas, but he was also an important mathematician and astronomer to the Royal Court. Omar Shakil himself, though not a poet, was a brilliant self-taught scholar, and certainly loved his telescope (although he was far more interested in watching the intriguing Farah than in observing the Milky Way). In a sense too, Omar Shakil was, like the first Omar, a courtier. Omar’s three mothers, the Shakil sisters, made sure that he would be a peripheral man until the moment of his death. Not only did he never find out who his father was, he didn’t even know which of his sisters was actually his biological mother. “Nishapur,” the enormous crumbling structure that was his home (named after the poet’s home) was located in between, as well as a little above, the English (“Angrez”) Cantonment and the native village. Most of the windows in this decaying edifice faced inward, and after the sisters’ infamous party, the subsequent sealing up of the great door and installation of the dumbwaiter, Omar learned to always face inward himself. He spent his formative years in splendid isolation and it is interesting to note that he spent a good part of his life living under other people’s roofs. Rushdie refers to Omar’s mothers’ “three-in-oneness” (p.31) and speaks of their “anchoritic existence” (p.12) and their “isolated trinity” (p. 6). There is a fascinating paradoxical element about all of this: we see the sisters as a type of cloistered nun on the one hand, and as sensual, obviously fertile women on the other. Omar comes into life “without divine approval” (p.15) the women later tell him that “his maker was a devil out of Hell (p. 308). The reader sees the mothers as the three Fates, the three witches of Endor, or a female Holy Trinity on the one hand, and also feels that they were innocent young women who were adversely and irreversibly affected by their own harsh prison like upbringing on the other. When Omar is reluctantly allowed into the outside world, the mothers tell him: “Don’t let them make you feel shame.” Rushdie interprets this to mean: don’t let them make you feel embarrassment, modesty, decency, the sense of having an ordained peace in the world—a “remarkable ban” (p. 34). Omar becomes an “invisible” man by becoming unashamed; by existing in a kind of “Eden of the morals” (p.13) and later by wearing nothing but unobtrusive grey clothing (p.136). Omar’s sense of inversion, his feeling of being turned upside down, turned inward, turned back upon himself, leads him to create his own sort of Cosmos. He feels that, because of the many earthquakes that were always occurring in the region, that Paradise must be underneath his feet and that the motion was caused by Angels emerging through the resultant fissures in the rocks (p.17). Therefore, Hell must be above, and limbo, that “third world” that was neither “spiritual or material” (p. 25) was where he lived. The religious fanatic Maulana Dawood accused him of descending to earth in “the machine of your mother’s iniquity” (p.173) meaning that Omar really came to earth from Hell; and of course, in the last descriptive paragraph, we do see his disembodied cloudy essence floating upward. Rushdie makes a political comment that Islamic fundamentalism is imposed on the people from above, (another subtle example of inversion) and we hear General Raza state the “the higher you climb, the thicker the blasted mud” (p. 223). Omar made the decision to escape from the “unpalatable reality of dreams into the slightly more acceptable illusions of his everyday life” (p.16). He trains himself to get by on “forty winks” in order to avoid these nightmares. Again, more authorial inversion. Rushdie cloaks (veils) things in fairy tales. Is he or isn’t he? Is this what it seems to be? Is that real or make believe? Should we feel sorry for Omar? Is Rushdie the narrator? Should we feel sorry for him? Is he or isn’t he talking about Pakistan—(he claims: “not quite.”)The reader follows Omar’s shameless degenerate trail, from Farah’s impregnation (through his use of hypnotism), to whoring and drinking with Isky, to marrying into the family that killed his half-brother Babar, to impregnating his wife’s Ayah (under his father-in-law’s roof, a particularly serious taboo), then to his financing of her abortion. Omar, because he never knew who his father was (only that he was told that he was “Angrez”), picked the foreign teacher, the kindly Eduardo as a surrogate. Omar himself, having no children—how do we really know that Farah’s child lived?—is himself an unknown father. He also receives censure from his mothers for being a sort of “absent father” to Babar (p.139). Although we see young Omar vomiting out his shame (at impregnating Farah while she was under his hypnotic spell) (p. 52) Rushdie shows that he later deliberately suppresses it “lest its explosive presence there . . . shatter him” (p. 84). Omar’s shame is signaled by dizziness which serves as a reminder of how close he is to the edge. He learns to distance himself, and in doing so makes himself into an “ethical zombie” (p.137). He is passive, a figure on the sidelines, a shadowy courtier. It is ironic that he becomes a famous immunologist. (He is adept at making himself immune to shame and this choice of profession is certainly apt.)His vertigo will only return when he finally goes back to Nishapur to face his shame, back to his birthplace “where you have been heading all your life.” His mothers had forbidden him to face shame and in the end, upon his return, had forced him to gorge upon it. He had even been obliged to immunize his wife Sufiya from shame—Sufiya, “his destiny” (p.153). Sufiya, the embodiment of shame, vessel of the world’s shame and shamelessness, who is saved again and again from destruction by Omar’s needle, who is rescued from being devoured by the beast of shame that occupies her body. Omar, himself an expert hypnotist, had looked into Sufiya’s eyes and seen “the golden eyes of the most powerful mesmerist on earth” (p.261)—certainly a diabolical reference. The time finally comes when Omar can no longer avoid the last confrontation with his shame. Back in Nishapur, the beast corners him and he is forced to recite a confession, a sort of litany of his own shameful acts. Omar, in facing his shame and taking on full responsibility for his shameless deeds, finally moves out of the wings and onto center stage. He actively plays his part and in doing so sacrifices himself to Sufiya. She in turn is consumed by the power of shame and blows up. There is a strange, never before consummation between husband and wife. At last they are free of shame, and they float up into the ether; Omar copying exactly his “adopted” father Eduardo’s stance that he had dreamt of long ago: lifting his hand in farewell (benediction?) like a headless genie—not going back into the magic lamp, but emerging from a vessel of shame up into hell. Here Rushdie continues his “veiling” and inversion. Is Omar, in death, finally free of sin (shame) and/or has he been consigned to his own inverted hell? Rushdie himself has mesmerized us and has also at times distanced himself from us, and in other instances, has drifted close to us. He operates on so many different levels and in so many different ways: practical, journalistic, and incisive, and, dreamlike storytelling, poetic. Who is Rushdie? Who is Omar? He could be Pakistan itself. His mother could be India and his father “Angrez.” He is a country divided, living in limbo, with a “mortal fear of falling into the void” (p.196).Perhaps this story is a veiled political warning to Pakistan. (Look what may happen to you if your shameful politics aren’t subdued. Poof! You may go up in a puff of smoke.) In retrospect we may also see it as a foreshadowing of what has happened to Rushdie, and what may happen to him in future. “Look what may happen to you if your shameful blasphemy isn’t subdued! You may go up in a puff of smoke”—Shazam!” Straight up into a Muslim hell. God forbid. Dictionary of Definitions “Angrez”: English/British Ayah: native maid, nurse or nanny Ayatollah: A title in the religious hierarchy achieved by scholars who have demonstrated highly advanced knowledge of Islamic law. Fatwa: A legal statement in Islam issued by a mufti or religious lawyer, which must be rendered in accordance with fixed precedent, and not an individual’s own will or ideas. A theological decision. Genie: (Jinn)-(Islamic mythology). Any of a class of spirits, lower than the angels, capable of appearing in human and animal forms, and influencing mankind for good and evil. Intifada: movement, uprising, protest. (Mainly associated with the Palestinian uprising against Israel.) Jihad: (Islam) To strive in the way of Allah. To fight in order to extend the bounds of Islam. A war against those who threaten the community. A battle, struggle, holy war for Islam. Can be used as a defense as well as an attack. Mufti: Muslim legal adviser consulted in applying the religious law. Qur’an: (Koran) Regarded by Muslims as the Word of God revealed in the Arabic language through the prophet Muham. Shame: The painful feeling arising from the consciousness of something dishonorable, improper, ridiculous, done by oneself or another. To cover with ignominy or reproach, disgrace. Shameless: Lacking any sense of shame. Immodest, audacious, insensible to disgrace. Brazen, unabashed. Hardened, unprincipled. Corrupt. Bibliography Freeman, John. Rocky Mountain News. Denver Post. November 3rd, 2002. Hourani, Albert. A History of the Arab Peoples. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1991. The Koran. (N.J. Dawood trans.) 5th rev. ed. London: Penguin Books 1990. Random House Dictionary of the English Language. Unabridged. New York: 1983. Rushdie, Salman. Midnight’s Children. Picador Ed. London: Pan Books Ltd, 1981. Rushdie, Salman. Shame. First Adventura Ed. New York: Random House, 1984. Rushdie, Salman. The Satanic Verses. Ontario, Canada: Penguin Books Canada LTD, 1988. Rushdie, Salman. Haroun and The Sea of Stories. New York: Granta Books/Penguin Books U.S.A, 1990. Rushdie, Salman. Step Across This Line. (Collected Fiction) 1992-2002. New York: Random House, 2002. |

Quinta: The Magical Number

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Teachers love school true.

Abbott Elementary.

Rome + Juliuss.

Clarence: We call him Mr. C ‘cuz he’s corny. But I like his class. It’s fun. He showed us Summer of Soul. That was good. He’s cool.