| | “All who wander are not lost.”—Tolkien

“Everything comes from somewhere.”—Rushdie

The way to avoid tragedy is to cultivate a sense of it” (Robert D. Kaplan). Aidan Chamber has said that the classic definition of story is: “What happens to whom, and why,” and since, as he reminds us, “story is everywhere,” we need to look everywhere in order to find exactly what it is we should be searching for.

We should start with oral tradition, with what Seamus Heaney calls: “the directness of utterance” by the skalds, bards, jongleurs, troubadours (and Rushdie’s the “Shah of Blah”), and from there progress through the arts up to the present.

A quest is a search or pursuit made in order to find or obtain something. There is a testing of some importance and obstacles to overcome. The goal or prize could be: The Holy Grail, hidden treasure, a castle or kingdom or fair maiden. It could well be something intangible such as: salvation, redemption, revenge, justice, peace, truth, glory, courage, strength, wisdom, faith, love, or hope. Sometimes one isn’t certain what it is that she/he seeks. Some fail, others do reach their goal.

The quest occurs in all types of literature, music, and historic events the world over, and all forms reflect the historical and cultural base in which they are embedded. There is a universality, however, a basic humanism about them all—a transcending core that resonates with everyone.

The quest can take the form of a grand and sweeping heroic epic, can appear in a short poem, a long narrative, an interior monologue, a small gem of a fable, a “pourquoi” story, a nursery rhyme. It can be found in certain films, music, plays, opera, novels, and rock songs. It can take the form of a chivalric romance, fairytale, folktale, mythology, legend, or nationalistic or religious saga. It can be emotionally heavy, or light and airy, and may contain both elements of tragedy and comedy. (Barzun points out that the word “tragedy” means “goat song” and in the Renaissance the word “comedy” meant any sort of play—drama in general.) He also states that the epic, thought of as a serious genre, is “often close to burlesque.”

The quest can be in the form of a cautionary tale, allegory, rules of conduct, a coming-of-age work or nationalistic propaganda. It can be gorgeous and soaring in tone, and heartwarming, whimsical, and quaint, or raw, ugly, and petty—but always passionate and always magic. It can entertain (hopefully, always), anger and disturb, instruct and uplift, enchant and inspire: one should come away thinking, analyzing, considering and questioning—and be receptive to and expressive about the core meaning of each story.

In each instance the characters could be any of the following: druids, oracles, pookas, banshees, piskies, kelpies, leprechauns, trolls, elves, menehunes, water sprites, Baba Yagas, dwarves, goblins, vampires, werewolves, ghosts, wizards, nissers, sorcerers, ogres, mummies, monsters, fairies, witches, queens, gremlins, brownies, golems, giants, genies, Black and Tans, angels, kings, dragons, devils, talking animals, and of course, larger-than-life heroic warriors (both male and female), their evil human counterparts, and naturally, a large cast of “common folk” such as farmers, innkeepers, “hoors,” hobbits, beggars, and children.

Props include: ancient books and parchments, thunder and fire, magic swords, cloaks, wooden legs, riddles and runes, shoes and lamps, talking cats, flying horses, snakes and toads, secret doorways and curses, spells, passwords, boats, bikes, rafts, umbrellas, whales, Cadillacs and taxis, dreams, visions, portents and nightmares, poisons and elixirs, trees and burning bushes, vast quantities of beer, wine, mead, and weed, and of course, gold rings.

Because, on the whole, we in this country have been exposed to mostly Western Canon, some may not be aware that there is a plenitude of much admired, and many revered, works of all genres that come from a global cultural base. Much of Western art, in fact, is based upon, or drawn from, ancient worldwide customs and lore.

The following is not meant by any means to be all-inclusive; the selections are certainly subjective. If they are top heavy with works from Great Britain, it is because (until fairly recently), our nation’s literary canon has derived mainly from and has glorified our “motherland’s” literature.

I Western

Great Britain and Ireland

The Cuchulain Cycle, The Finn Cycle, (Fin M’Coul), two pre-Christian Celtic epics: The Hound of Ulster and Queen Mab. Beowulf: Anglo Saxon epic Christian poem composed sometime between 650 ad and 900 AD. Seamus Heaney, Irish Nobel Laureate Poet, renders a brilliant translation. King Arthur, Knights of the Round Table, Merlin, The Holy Grail, and Robin Hood. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (author unknown). The Crusades, St. George and the Dragon, William Langland’s Piers Plowman, Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, the Welsh White Book of Rchydderch, Sir Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d’ Arthur. Morality plays and mystery plays for example, Everyman, dramatized allegories of Christian life: a quest for salvation.

Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, Shakespeare’s English and Roman histories, tragedies and tragic-comedies. He was extremely knowledgeable about the volatile social and political issues of his day: the escalating patriotism and nationalism, the new colonialism, and concerns about the royal succession. A.L. Rowse tells us that he (Shakespeare) “. . . knew too well how thin is the crust of civilisation; how easy for society to break down, to fall into what dark waters beneath.” In these works, Shakespeare’s quest is for order and obedience to authority.

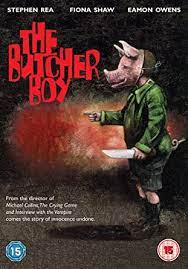

Milton’s Paradise Lost, John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders, Richardson’s Clarissa, Fielding’s Tom Jones, Edward Fitzgerald’s (translation) The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam, Wordsworth’s The Prelude, Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan, Blake’s The Four Zoas and Jerusalem, Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, Keat’s Hyperion, The Eve of St. Agnes and La Belle Dame Sans Merci, Byron’s Childe Harold, Sir Walter Scott’s historical novels and ballads, Dicken’s Bleak House, David Copperfield, Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities, Robert Browning’s Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came, Tennyson’s Ulysses and Idylls of the King, Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Kipling’s Just So Stories, Sir James Barrie’s Peter Pan, Hugh Lofting’s Dr. Doolittle, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh, P.L. Travers’ Mary Poppins, Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit, James Joyce’s Ulysses, Yeats’ Fairy Tales of Ireland, T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Ring Trilogy, C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, Roddy Doyle’s A Star Called Henry, J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series

North America

Highwater’s Anpao (the Native American Ulysses) The Sedna Legends of the Inuits, Paul Bunyan’s tall tales, the tales of Pecos Bill the Cowboy, Melville’s Moby Dick, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus Stories (a retelling of stories brought from overseas by African slaves), L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, the Russian born Nabokov’s Lolita, Steven Spielberg’s E.T., and, with George Lucas, the Indiana Jones sagas and Star Wars series.

French Canada

The Adventures of Petit Jean

Mexico/South America

Why the Burro Lives With Man, The Tale of the Lazy People and many legends and myths from the Incas and Aztecs and Mayan civilizations

Greece

Homer’s The Iliad, The Odyssey, Aesop’s Fables

Italy

The Roman poet Virgil’s The Aëneid, the poet Dante’s The Inferno, the poet Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered

Spain

El Cid (the epic poem El Cantar de Mio Cid), Cervante’s Don Quixote

Portugal

Comoën’s The Lusiads

France

The deeds of Charlemagne, Le Chanson de Roland, Jean de Neun’s Roman de la Rose, La Fontaine’s Fables, Perrault’s folktales (Cinderella), Villanueva’s Beauty and the Beast, Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo, Saint Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince, de Brunhoff’s Stories of Babar

Germany

The Nibelungen Saga (heroic sagas), the tales of the Brothers Grimm, Richard Wagner’s Opera Cycle: The Ring of the Neibelung

Norway/Sweden/Denmark

The great sagas involving Valhalla and the gods Thor, Odin, Freya, and Loke; Hans Christian Andersen’s tales

Iceland

The Elder Edda, The Younger Edda (ancient manuscripts), from these comes The Volsunga Saga

Finland

The saga The Kalevala

Russia

The Legend of the Firebird, Pushkin’s fairy tales, Vasilissa the Fair

II Middle East

The sacred texts: The Holy Bible, The Torah, The Talmud, The Koran. Firdavsi’s Shah (collection of legendary Persian epic folktales), the splendid Arabian Nights, the Islamic legend The Night Journey (Mohammed’s Night Ride to Heaven) Nobel Laureate Isaac B. Singer’s Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories

III India

The Fables of Bidpai, The Jatake Tales of Buddha, the cycle of fables in the Hindu collection of the Panchatantha, Vyasa’s Mahabharata, Valmiki’s Ranayana, Salman Rushdie’s Shame and Haroun and the Sea of Stories

IV Africa

Tribal tales of witchdoctors and brave warriors, folktales like Anansi the Spider, Podhu and Aruwa, Unanana and the Elephant

IV Far East

Japan

Great shogun and samurai exploits, folktales such as The Tongue-Cut Sparrow, The Enchanted Sticks

China

Fantastic tales of empresses and peasants, warlords and courtiers. Folktales like Ah Tcha the Sleeper, The Story of Wang Li

V Oceania (Australia)

The wonderful Aboriginal “dream-time” experiences and folktales such as Dinewan the Emu

Polynesia

Many fantasy tales of how their islands were fashioned; from Hawaii we get the myth: How Kana Brought Back the Sun and Moon and Stars. To quote Heaney, all of the foregoing are universal stories of “mythic potency.”

To return to the main question: What should we be looking for, and why? Tolkien said: “Myth is invention about truth.” Joseph Campbell states that the hero’s journey is about “overcoming the dark passions . . . to control the irrational savage within us,” and that “the journey is a life lived in self-discovery . . . the ultimate aim of the quest must be . . . the wisdom and the power to serve others.” The hero acts “to redeem society.” Dostoyevsky said: “Man is a mystery.” The author was “an investigator of the human spirit” always searching for truth. In Richard Tarnas’ preface to his grand The Passion of the Western Mind (and this could certainly apply to the rich and varied canon of world literature as well), he states: “The history of Western culture has long seemed to possess the dynamics, scope, and beauty of a great epic drama . . . [containing] sweep and grandeur, dramatic conflicts and astonishing resolutions . . . a stirring adventure and epic heroism . . .” He also talks about: “A common vision . . . to see clarifying universals in the chaos of life . . . the attempt to comprehend the nature of reality.” Bruno Bettelheim says that through fables and fairy tales we can find ways “to gain peace within ourselves and with the world . . .” In a new volume of Yeat’s essays, Writings on Irish Folklore, Legend and Myth he tells us that in fables, “mortals are transformed into ‘perfect symbols of the sorrow and beauty and of the magnificence and penury of dreams.'” Harold Bloom feels: “We read to find ourselves . . .[to gain] an enhanced sense of freedom . . . to prepare ourselves for change and the final change, alas is universal.”

Certainly there are skeptics among us: the poet W. H. Auden said: “poetry makes nothing happen” and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road narrator (“the road is life”) says “. . . nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old . . .” And U2’s Bono laments “. . . and I still haven’t found what I’m looking for.” To all that, Tolkien’s Gandalf could well answer: “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

During the rest of our lifequest we must: read, write, travel, attend plays, opera, museums and films, watch television and sporting events, listen to music, political debates, talk shows, gossip, and propaganda. We must sing and dance and work and love, all so that we may connect in some positive and meaningful way with our ancestors, peers, and children, thus hopefully discovering our higher selves. By doing so, when our grand quest comes to the inevitable and unavoidable end, we will be able to leave behind a brilliant, universal ensemble cast with a balanced and harmonious script full of recurring motifs such as unity and integration, a magnificent work, a gift of love and peace to our vast audience—all of humankind’s descendants.

“The world is sacred,

It can’t be improved.

If you tamper with it, you’ll ruin it.

If your treat it like an object, you’ll lose it.”—Lao-tzu

Bibliography

Barzun, Jacques. From Dawn to Decadence. New York: HarperCollins, 2000.

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment. New York: Simon, 2000.

Bloom, Harold. How to Read and Why. New York: Simon, 2000.

Campbell, Joseph. The Power of Myth. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

Chamber, Aidan. Introducing Books to Children. 2nd ed. Horn, 1983.

Doyle, Roddy. A Star Called Henry. New York: Penguin, 2000.

Heaney, Seamus. Beowulf. New York: Norton, 2000.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. New York: Viking, 1957.

Lao-tzu. Tao Te Ching. Trans. Stephen Mitchell. New York: Harper, 1988.

Maxym, Lucy. Russian Lacquer, Legends and Fairy Tales. 2 vols. New York: Siamese Imports, 1985-86.

Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. M.H. Abrams. 5th ed. 2 vols. New York: Norton, 1986.

Oxford Companion to the English Language. Ed. Tom McArthur. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1992.

Porcaro, Lauren. “Book Currents”: rev. of Writings on Irish Folklore, Legend and Myth by William Butler Yeats, New Yorker 1, Apr. 2002: 21.

Riverside Anthology of Children’s Literature. Judith Saltman. 6th ed. Boston: Houghton, 1985.

Rowse, A.L. The Annotated Shakespeare. Vols I and II. New York: Clarkson, 1978.

Rushdie, Salman. Haroun and the Sea of Stories. New York: Viking, 1990.

Tarnas, Richard. The Passion of the Western Mind. New York: Ballantine, 1993.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Hobbit. New York: Ballantine, 1967.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Ring Trilogy. New York: Ballantine, 1982. |