by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

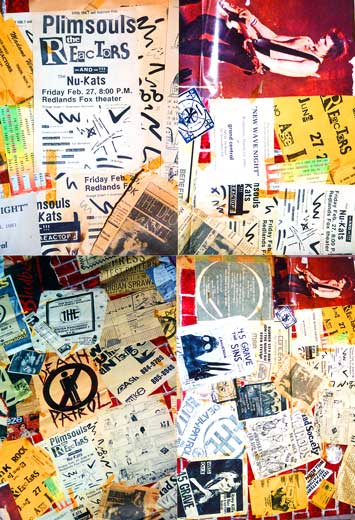

Bryan Knox was born under the sign of Virgo to a dichondra farmer in Riverside—when the area code was still (714). Virgoans are custodians of culture—and true to his astrological sign, Bryan’s early punk rock years are filed chronologically (1980-88), geographically (Los Angeles, Orange, and Riverside Counties), and neatly in a box marked “Punk R#ck Doc. Destroy Date: Never.” Content is divided between “Stuff I did” and “Stuff I didn’t.”

Bryan’s collection, and his clear recollection of the punk crowd: poets, artists, writers, trust fund babies with gangster daddies . . . not to mention the musicians that laid down the soundtrack to L.A.’s early punk rock party—makes it easy to go trippin’ down memory lane.

Exene

“What’s black and white and read all over?”—Children’s Riddle

Bryan: It was 1978 or 79. My friend Bill Bartell and I finagled this gig with the The New Rocker. The office was in the 9000 building across from The Roxy on Sunset Boulevard. We would hang out and pretend to be important. No one was ever really working anyway, the job was just leverage to go see bands. We heard X was playing at the Hong Kong Cafe. We arrived early to watch the sound check. At one point Bill and I were sitting around with John Doe and Exene and DJ Bonebrake. I was naïve to their personal history. John Doe’s gear had stencils of Baltimore all over it, his bass case, et cetera. I asked him about it. He said it was because he was from Baltimore, which surprised me, I don’t know why.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Maybe, because even then he was emblematic of Los Angeles.

Bryan: Exactly. Exene was looking through the LA Weekly. She would stop on different pages to color over photographs. Every once in awhile she would open her cigar box and very carefully select a new crayon. I looked in the box. All the crayons were red.

Joan Jett

“We like dancing and we look divine”—Joan Jett [sings a David Bowie tune]

Today’s artists hire their own “people” to keep the masses away. At least, at bay. In the early L.A. punk rock scene, it was fairly easy to mix with people now elevated to icon status. Like Exene and Joan Jett.

Bryan: I was living in Moreno Valley. Darby Crash was still alive. A bunch of punk bands were playing at Great Gatsby’s in Redondo Beach. The Angry Samoans, Eddie and the Sub-Titles, the Circle Jerks, maybe. I drove a 68 Volkswagen Squareback. Bill Bartell, Jon Morris, Donnie Rose, and I had a TEAC open reel four-track recorder that we took to all the shows. We’d arrive at the door and say we’re recording the band—then we’d go to the soundman and say we need two lines out of the board and he would plug us in. We would use two mics . . . which reminds me of another story that you can’t publish because it’s too criminal . . .

That night we got into the club but the soundman was onto our scam and wouldn’t let us record, so we just watched the show. I noticed Joan Jett standing dead center in front of the stage, teetering. Everyone slamming around her. She was barely conscious, having a good time. Jon was a big fan of Joan’s and thought we should try to talk to her, but Bill said: “No,” we should try to kidnap her. We discussed the pros and cons—wouldn’t it be funny and cool and punk rock? But then she would find herself in Riverside.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: BUST Magazine sells the t-shirt W.W.J.J.D? What Would Joan Jett Do?

Bryan: What would Joan Jett do? She’d be mad and we’d get our asses kicked and she would dislike us. And we’d have to drive her two hours back to L.A.

The Ramones

“Rock, rock, rock’n’roll high school”—The Ramones

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻:How did you get into punk rock?

Bryan: I can’t really remember what I listened to as a kid besides the usual—like The Beatles. Then in TV Production class at Moreno Valley High, 1978, I met Jon Morris. Jon was into audio recording—he had recording equipment and a serious stereo system. The only thing I had was an eight-track player in my Ford pickup. It was stolen when we went to see the Ramones open for Black Sabbath at Santa Monica Civic. He also had a Punk Magazine. Jon, Bill Bartell, and I would sit around and listen to records, reading Punk and other zines. We were aware the Sex Pistols were touring. We tried to figure out a way to get to San Francisco to see the ultimate punk rock concert. We never made it, but we spent a lot of time obsessing over it.

Bill Bartell knew this girl named Nikki who was Donnie Rose’s girlfriend at Poly High. Nikki called herself Sheena because all girls called themselves Sheena—because of the Ramones. Sheena and Donnie were a punk rock couple.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Isn’t there a Donnie Rose—Germs connection?

Bryan: He was definitely a Germs insider. Donnie was really young when he got into the punk rock crowd. Before high school. Anyway, he and Sheena had a friend named Rene Gade. I met her at The Squeeze, a little nightclub in Riverside, run by Nicki Syxx. Rene was the first real punk rock girl I ever saw. Beautiful and cool with exaggerated make-up and spiky short hair. Beautiful and cool.

Death Patrol

“Looking out the window and who do I see? Someone outside is glaring at me.”—Rene Gade

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: Were you ever part of a band?

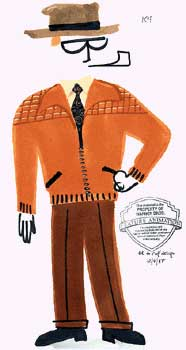

Bryan: Yes. The early 80s was the first time Death Patrol performed. Bill Bartell instigated the band for his own amusement. He was always there, but he wasn’t in it. I was the bass player. Well, it was really an old Japanese guitar that I put bass strings on, which was fine since I didn’t know how to use it anyway. Jon Morris “operated” the synthesizers and was the guitarist. We didn’t have a drummer. Shawn Cowart was the singer. We called him Warcot—Cowart inside out. He was an illustrator—gory comic book art with pop culture commentary.

The original lineup played twice. Shawn lost interest. Jon lost interest. Rene joined the band. Then her friend Stacy joined—she played guitar. Like most bands, Death Patrol went through quite a few mutations. We really wanted to be the Screamers. We made up a story about how we opened for the Screamers. Other bands corroborated our story—it eventually became an urban myth.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻: There’s a flier in one of your files: “The Alternative Alliance for the Inland Empire” advertising for drummers for three different bands, including Death Patrol. Requirements include: “Punk as in early Clash, Stiff Little Fingers, and other British Punk Bands. This isn’t H.B. [Huntington Beach]. Dark romance, avant-garde. Prefer creative person not influenced by Black Flag. Determination over skill.”

Bryan: The Alternative Alliance was the tagline for different projects—to make it sound more organized than it really was. We did have rehearsal space, though. I had rented a one-bedroom house; the previous tenants had modified the garage into an acoustic, insulated sound studio. Serendipitous.

🆆[🅱🆃]🅻:Was Death Patrol any good?

Bryan: No, we were terrible. But if you’re creating your own fun, everyone has a reason to have a good time. It didn’t matter if you were good—it only mattered if you were entertaining.