by Kerrin Ross Monahan

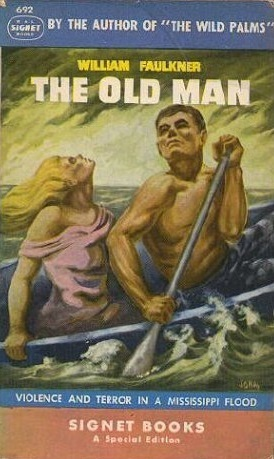

| In William Faulkner’s short fiction, The Old Man and The Bear, the author uses a convict and a bear as protagonists of their respective stories. In a strange way, the tall convict and the animal both represent the same thing. They each stand for a certain purity, and innate innocence, in the face of an increasingly evil and disintegrating society. It is clear Faulkner feels the world encroaching upon the bear, and the world outside prison walls—is civilization at its worst, or at least a culture rapidly becoming that way. The Old Man stands for the Mississippi River, a symbol of life itself with all its vicissitudes and unforeseen mishaps and tragedies. Restless, unpredictable, and powerful, it can obliterate and sweep away everything in its path. The story takes place in Mississippi, 1927. The tall convict, an unschooled rural type, is serving a fifteen-year jail term for attempted train robbery. The staff volunteers certain inmates to help in an emergency rescue operation brought on by a flood; thus Faulkner puts his character back in the midst of the same civilization he felt had misused the young man. It should be noted that the Deep South has traditionally had a far more conservative and repressive penal code than possibly anywhere else in the United States. Faulkner immediately depicts what he felt were societal faults. We hear the story of the short and plump convict who was given an outrageous sentence of one hundred and ninety-nine years—for a murder he didn’t commit. In very strong terms, the author asserts those acting on behalf of the law were: “blind instruments not of equity but of all human outrage and vengeance, acting in savage personal concert . . . which certainly abrogated justice and possibly even law.” In the end, the tall convict (with eight years left on his sentence) is given an additional ten because, when he hadn’t immediately returned from his rescue assignment, he had been officially declared dead on paper, and the prison officials wouldn’t change anything for fear of making themselves not only look foolish, but also for fear of political repercussions. Faulkner not only attacks the iniquities of the legal processes, but racial prejudice as well. One white evacuee is indignant at the fact the rescue launch is too full to take him: “. . . no room for me . . .”Another symbol of the society that had let the tall convict down was the pregnant woman he had rescued from the waters. He had spent weeks taking care of her amidst the most perilous of conditions, but the reader never sees or hears her thank him in any way whatsoever. His teenage girlfriend that he describes in the very end, quite possibly the cause of his attempted robbery, had only visited him once in jail and then sent a postcard announcing her marriage. His last words: “Women, _ _ _t” sums up the betrayal he felt toward the opposite sex. It is then no wonder that the tall convict views life behind bars as a “comparatively safe world.” He saw the outside world as a “separate demanding threatening inert yet living mass of which both he and she (the pregnant woman) were equally victims.” Prison to him was “home, the place where he had lived almost since childhood, his friends of years . . . the familiar fields . . . the mules . . . barracks [with] good stoves in winter . . . food . . . Sunday ball games and the picture shows.” All of this certainly does evoke a comforting and homelike atmosphere. Even though, near the end of his adventure, he realizes he had “forgot how good it is to work” and make money, after he was safely back in the barracks he felt that he was then secure from the “waste and desolation” the Old Man represented. It is as if everything had been reversed: the real world, comforting and familiar was in jail, and the life outside was confusing and frightening. Because the convict had accepted his lot in life and possessed a strong feeling of duty, he is, in a certain way, free. The Bear spans approximately eleven years, from 1877 to 1888, when Ike, the young boy, grows from age ten to twenty-one. In the beginning, Faulkner sees the bear, Ben, as free, a formidable legend of the forest. He invests the animal with wisdom and dignity and there is a worthy, although adversarial respect between him and Ike. Faulkner gives us his own feeling in the very first paragraph: “. . . only Sam Fathers, Ike’s mentor, and Old Ben and the mongrel Lion were taintless and incorruptible.” He speaks of the natural landscape as “that doomed wilderness where edges were being constantly . . . gnawed at by men . . .”Sam’s father was the son of a Negro slave and a Chickasaw chief and it is he more than anyone else who teaches Ike to have respect, almost a great reverence, for nature. Certainly, he is anxious to track down Ben, but when he had the chance, he didn’t kill him, because, as Ike said: ” . . . it (the killing) won’t be until the last day, whenever he don’t want it to last any longer.” When the hunter Boon and the dog Lion finally kill the bear, Old Sam “collapses because he knows this is the “last day,” the end of an era, not just of his own life, but also of the pristine wilderness. Sam had successfully passed on his reverence for life to Ike and it is he who makes a primitive pyre for Sam and the dead dog. Faulkner uses racial prejudice in this story as well, to show what he thinks of the world. At first, Part Four seems out of place, a complicated genealogy in the form of a family diary. These records show there is African American blood back in the family history. Through this device the author exposes the exploitation and mistreatment of the American Natives and Black slaves by the Whites. The author then states that man should: “Hold the earth mutual and intact in the communal anonymity of brotherhood . . .”In the end, progress invades in the form of the lumber company. Major de Spain, one of the original hunters, had sold out and a new planing mill is built. The log train, that had once simply been an unobtrusive way in and out of the forest for hunters, now had become something more menacing: “It was a doomed wilderness. . . . The shadow and portent of the new mill . . .” Ike himself, now twenty-one, at this moment knows he will never return to the old hunting site again. Faulkner then invokes the “trinity” of Sam and Ben and Lion, a kind of resurrection: “There was no death, not Lion and Sam . . . and old Ben too . . . not held fast in earth but free in earth and not in earth but of earth . . .” In dying, this trio took with them the last of the old revered way of life that can only be born again in the hearts and minds of human beings. Faulkner’s view of the worlds in which these two stories take place is rather dim and negative. Society, in the name of progress, is destroying, unchecked, a pure and innocent world. The tall convict instinctively and ironically retreats back to the safety of man-made bars in the face of nature gone amok. The bear, with a similar kind of instinct, deliberately lets himself be caught and killed; death being a safe retreat from man gone amok. Neither story holds out much hope for the future and it is clear that Faulkner had little faith in society’s ability to foretell and correct these cultural ills. Work Cited Faulkner, William. Three Famous Short Novels: Spotted Horses, Old Man, The Bear. New York: Vintage, 1961. |