by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Children Run Pell Mell.

The Happiest Place on Earth.

Hell or (Hi!) Daughter.

Fig. It. Out.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Children Run Pell Mell.

The Happiest Place on Earth.

Hell or (Hi!) Daughter.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

Velocity Blur.

Scintillating Gyration.

Va-Va Voom Vroom Vroom.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

“Why is she talking?”

Koo-Aid Intoxicated.

Lucky Lady Goals.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

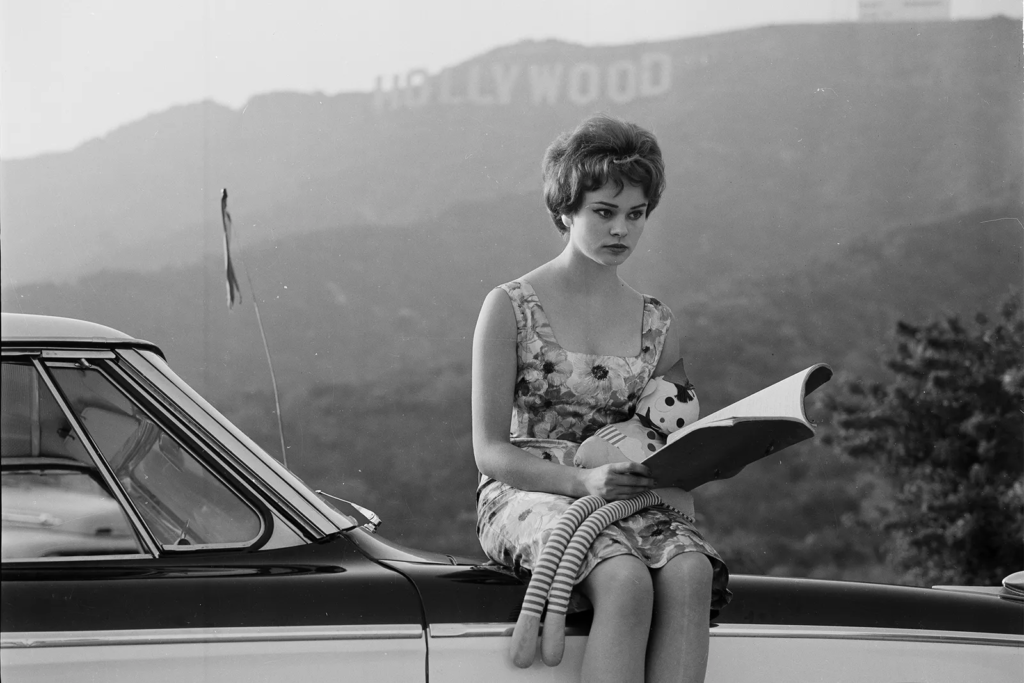

Glamour flies Dem breaks.

Hollywood walk of shame lies.

You are what you ate.

Pretty & Darn Quick Reviews by Various & Sundry Rabble Rousers

“. . . she’s not even reviewing a film, she’s telling you how clever she is.”— All That Jazz

• About a Boy Charming: the boy Marcus. Disarming: the boyish Hugh. Alarming: junior high, “Lorena Bobbit for Surgeon General,” and the mournful mama Marcus has on suicide watch. Barmy Brits and karmic bits make it “smooth and winning.”

• About Schmidt Another comedic lecture in Professor Payne’s American Social Studies course, or an overlong infomercial? I found it disconcerting that a commercial for Childreach, the international child sponsorship organization that is Jack Nicholson’s character’s salvation, aired in the movie theater right before the critically lauded film began. Admirable indeed, to “promote the rights and interests of the world’s children,” but, just as I like to choose my movies, I like to choose my charities.

That said, About Schmidt offers an idiosyncratic look into middle-class middle American lives—character studies made unforgettable with an excellent ensemble cast àla Citizen Ruth and Election.

• Across the Universe “Have you seen it? It’s great. They’ve got stuff.” — Eddie Izzard for the benefit of Mr. Kite.

• Adaptation “Do I have an original thought?” When writer Charlie Kaufman questions his genius, the answer comes back in the form of a pastiche perfect follow-up to he and fellow original thinker Spike Jonze’ Being John Malkovich. Catherine Keener plays Boggle!—an apt metaphor for Kaufman and Jonze’ mind game antics.

• Alpha Dog The ballad of Jesse James Hollywood: Mama, don’t let your babies grow up to be drugstore cowboys.

• Amélie A perfect Parisian ensemble of innocence and cynicism.

• Arrested Development Step behind the Orange Curtain for a delicious Balboa Bar and a Gob Bluth bon mot: “These are lawyers. That’s Latin for liar.”

• Australia Baz in Oz. Great expectations, punctured by over-inflation.

• Babel The way of the gun.

• Barton Fink “I can’t start listening to the critics, and I can’t kid myself about my own work. A writer writes from his gut. His gut tells him what’s good, and what’s merely “adequate. . . . If I ran off to Hollywood now, I’d be making money, going to parties, meeting the big shots, but I’d be cutting myself off . . . from the common man.”

• Big Fish Fresh, charming, delightful. Suspend your disbelief, (as we must do in our lives). As Balanchine said: “Non-reality is the real thing.”

• Big Love (polygamous Ring around the Rosie) and Saved! (JC GRL and her girl gang for Jesus) both use the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows” for a theme song. ACDC’s “Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap” might be more àpropos.

• The Big Picture This 1989 gem should be required viewing for every film school grad. Once again, writer/director Christopher Guest proves he is ahead of his time:

Building Manager: You know who used to live here?

Nick: No, I don’t.

Building Manager: Take a guess. Very famous.

Nick: Clark Gable?

Building Manager: Nope. Guess again.

Nick: Marilyn Monroe?

Building Manager: Nope.

Nick: Errol Flynn?

Building Manager: You give up?

Nick: I give up.

Building Manager: Chuck Barris. The Gong Show guy.

• Blades of Glory Boxers, briefs, or spectacular spandex?

It’s no Ice Castles, or Zoolander for that matter, still and all, just the concept of (ex) married couple Will Arnett and Amy Poehler playing brother and sister is comedy gold.

• Blue Crush: North Shore, but with girls.

• Boarding House: North Shore Punch Drunk love.

• The Bourne Identity Ready. Set. Go! Ms. Potente sprints through Run Lola Run, then dashes with the dashing Matt Damon in Doug Liman’s stylin’ international thriller. Next film out, Franka says relax! Or at least she should.

• Carnivàle There’s no biz like showbiz, even amidst titanic rust colored dust storms in depression era Oklahoma:

Samson: I’m about to make you the offer of a lifetime. . . . How would you like a career in showbizness?

Ben: What’s the wages?

Samson: Nothing at first . . .

Tales told of the curious carnies’ code. DiVine DuVall. John Savage. John Doe. Samson the Magnificent. God and Babylon. . . . Yes, join this circus.

• Catch Me If You Can runs long. The film’s trailer and titles con you into believing it’s a keen comic flick—a nifty 60s biopic of the fumbling FBI and a scam(p) on the lam. At its core, however, is a melancholy tap dance between father and son. Still and all—a swell spin across 2 hours and 20.

• Chicago Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz is a rapturous musical feast—Chicago, written by Bill Condon and directed by Rob Marshall (based on Fosse’s stage version), is the razzmatazz cocktail to swill beforehand.

• Cold Mountain Beautiful scenery, fantastic music, especially in church’s “space” singing. Renee got all of the good lines (and the Oscar). Horrific battle scenes. A great diatribe against war, and what it can make normal people do, and it certainly exacerbates the already nastiness of terrible people. Minghella talks of “tribalism” North vs South, and, even after all of these years, I found myself disliking Southerners, despite my own Southern roots.

• Confessions of A Dangerous Mind With his latest endeavor, George Clooney proves he possesses more than bankable good looks—he also has an uncanny talent for directing. Utilizing genre-specific film techniques, Clooney escorts the audience through the adventures of Chuck Barris’ life. There is a surprising subtlety to the tone and performances in this picture given the strange and often fantastic events therein. Are the incidents real? Viewers won’t care—they’ll just be happy to have been privy to the Confessions.

• The Curious Case of Benjamin Button Time-ravaged Brad, ravishing timeless Cate, moments borrowed from Forrest Galump, stolen moments from Magnolia. It’s small fry in a Big Fish pond.

• The Darjeeling Limited If you must pack your bags for a guilt trip, you might as well have matching Marc Jacobs (for Louis Vuitton) monogrammed suitcases. And a laminator. All that’s missing is a tea set for Frances.

• The Dark Knight Christopher Nolan’s sleek, yet long and winding road of a film is hijacked by Heath, the rare avis behind the jocund Joker — and Gotham’s mighty maelstrom: “I believe what doesn’t kill you makes you stranger.” Sigh.

• A Decade Under the Influence Auteurs articulate recollections of 70s films that were not just “canaries in a cage” — but viable life forces that effected cultural change. Prescient to what would happen once they hit the big time are found in an exchange between Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper’s characters in Easy Rider:

Peter: You know Billy . . . we blew it.

Billy: What? . . . That’s what it’s all about, man. . . . I mean, you go for the big money and you’re free, you dig?

Peter: We blew it.

Gracious is the wish these “easy riders raging bulls” hold for the new generation of filmmakers who interview the filmmakers for the Decade documentary: that is to continue to follow their dreams on the path of independence.

• Donnie Darko Graham Greene’s short story The Destructors is the thematic thread tied to writer/director Richard Kelly II’s exceptional indie film. To the purpose in these dark times.

• Down with Love Ewan McGregor as Catcher Block may act like a dog in his hounds-tooth jacket, but he really is the cat’s pajamas in this spritz of a film that winks at the war between the sexes while it works its 60s fashion sense.

• Dreamgirls Jennifer Holliday or Jennifer Hudson? Each imbue girl group standout Effie: one singular sensation.

• Eight Legged Freaks Add Arachnophobia and Tremors, subtract all campy humor and Kevin Bacon and you end up with Eight Legged Freaks. A poor excuse for a “camp classic,” it has little going for it other than a stylized marketing campaign. The most entertaining thing about the entire ninety minutes was the guy who sat behind me interjecting comments like: “They cocooned his ass.” If only someone would have cocooned the asses of the filmmakers, I would have been spared this lame mutant spider mess.

• 8 Mile Director Curtis Hanson may have indulged in risky business hiring Eminem as the imitation of the real Slim Shady’s life, but he sure played it safe with writer Scott Silver’s formulaic script. Eminem acquits himself nicely as an actor, and is particularly good in the rare moments of humor (check out he and Mekhi Phifer’s rap to the tune of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama”). Lacks the idiosyncratic characters of the fabulous Wonder Boys and the dark complexities of L.A. Confidential, but you sure can’t beat the authenticity of the slammin’ soundtrack.

• Entourage: One Day in the Valley

Drama: Vince, you know my policy. Except for work, I only go to The Valley November through March. And even then, only to Sushi Row.

Vince: C’mon Johnny, go for me.

Drama: I’d better hydrate.

By the episode’s end, Drama realizes what all of us Valley Girls already know: “Yeah, The Valley ain’t so bad.”

• Fantastic Mr. Fox Truly Scrumptious.

• Far From Heaven Gorgeous costumes, Technicolor-coordinated with the 1957 sets (Julianne Moore’s speckled winter coat matching the movie theater’s granite foyer is a stylish storytelling touch), illuminate ugly issues that have yet to be resolved. Many women in this millennium either do not recall, or recognize, the feminist movement. Ms. has reverted to Mrs. without anyone batting a false eyelash. Now that’s a real tearjerker.

• Finding Nemo Disney’s dementia division: When Pixar’s kids are bad, they’re horrid; remember vicious Sid in Toy Story? Dental (im)patient Darla’s no darling in Nemo; she and ditzy Dory swim away with this undersea story.

• Flight of the Conchords Watch this absurdist Kiwi comedy, and you will burst into song, just like Jemaine and Bret: “You’re so beautiful, you could be an air hostess in the sixties.”

• Glee “Well, if you want to sing out, sing out/And if you want to be free, be free.”— Cat Stevens as featured in Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude. William McKinley The Go-To school for Glee and the E.L. Konigsburg classic, Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth.

• Good Night and Good Luck You stay classy George Clooney.

• Kathy Griffin: My Life on the D-List Funny girl Kathy is just like us. My case in point, in Season 1, episode 5, The New York Times photographer Stephanie Diani arrives to shoot the star for Griffin’s “The Red Carpet’s Bête Noire” 2/27/05 article. Stephanie okays the crooked tiara, suggests messy hair, and politely turns down Kathy’s “any chance you can retouch the photo” entreaty — just as she did when I whined about the photo for Oπe® & my “TiVo, Cable or Satellite? Choose That Smart TV Wisely” 9/5/04 interview (written by Ken Belson). Not to worry, Stephanie “Baby, make me a star” Diani does just that with her elegant eye and egalitarian camera.

• Gran Torino Cliché driven.

• The Great Gatsby (as referenced in Best Laid Plans)

Bryce: So we have survey courses to start, American Lit, Brit Lit, everything that should be taught in high school: Hawthorne, James, Fitzgerald.

Nick: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly with the past.” F. Scott. Great Gatsby. That’s a book he wrote.

Bryce: We don’t actually read anything we teach. The department chair gives us Cliff’s Notes at the beginning of the semester, and we just say whatever’s in those.

• The Grim Reaper According to TV cult show Dead Like Me, Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones, and Woody’s latest Scoop — the sweet hereafter ain’t so sweet. Unresolved issues, investigations, and menial jobs take up valuable resting time. Thank God for the black humor death informs.

• Grindhouse Guns, Gals, Ghouls, and Gore a GoGo! Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino’s double feature issues the following warnings:

Don’t blaspheme.

Don’t call a Kiwi an Aussie.

Don’t take rides from strangers.

Don’t mess with Texas.

(Do, however, see Planet Terror and Death Proof, they’re Supersonic.)

• Hamlet 2 “The play’s the thing” becomes more playful with a snackatorium and Cricket in Times Square.

• Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets The trouble with Harry Potter isn’t Harry at all—it is the action and events that transpire without enough exposition in a story that, ironically, is far too long. Dobby, the Jar Jar Binks-ish character, is an elfish irritant. Moaning Myrtle haunting the loo and Kenneth Branagh’s love affair with himself, however, are magical fun.

• Heist David Mamet’s capable caper flick. It’s not wordplay — it’s wordspar.

• The Hoax Richard Gere moves with his gigolo groove but it’s Alfred Molina who really pulls off The Hoax.

• Holes Dig it.

• Hot Fuzz With both barrels blazing, the Brits bust the buddy cop genre to bits. Bloody good!

• I Love Your Work

Louis: He’s not a stalker, he’s a fan.

Gray: And Mark Chapman just loved The White Album.

Louis: Well, it was a good album.

• Inglourious Basterds Proving to schoolchildren everywhere: you can misspell and still write well.

• Insomnia These are the questions that keep me wide-awake. What happened to Paul Dooley? He disappears at some point in the movie. Why did Hilary Swank go to an only just released suspect’s home without backup? Why do grown men reference Star Wars in daily conversation? (Okay, Nicky Katt’s Obi Wan bit is funny.)

• Iron Man It may be Robert Downey Jr.’s rodeo, but to fans of Susan Pickett (not limited just to Annie Liebovitz and RC McGowan), it’s her visual effects show.

• Juno Screenwriter Diablo Cody knows who wears short shorts: Michael Cera! Superbad.

• Keen Eddie starring American actor, Mark Valley, as a U.S. police detective working in London with Scotland Yard. Quirky and quick; Valley is beautifully supported by topflight (Is there any other kind?) British “character” actors.

Inspector Monty Pippin: You, see, the key to understanding the English is not what they say, but the inflection. . . . the inflection implies the intention.

Detective Eddie Arlette: Well, give me a for instance.

Inspector Monty Pippin: When Sir Edward asked how my brother Tom was getting along, what he really meant was, I know where you live, you bastard. You and your brother will be living in a rubbish bin by the time I’m through with the lot you . . .

• The Kid Stays in the Picture Robert Evans animatedly revisits his decades under the influence through signature oversized rose-colored glasses.

• The Last King of Scotland Forrest Whitaker’s performance as a beleaguered high school principal is quite competent in the R-rated after-school special American Gun. Skip it and see his embodiment of Idi Amin instead.

• Lilo & Stitch Orphans! Aliens! Elvis! It doesn’t get more American “ohana” than that.

• Love Actually A wry slice of sigh.

• Lovely and Amazing is exactly that. In particular, the brief, yet multi-layered moment between Catherine Keener and heartbreaker Raven Goodwin. Rife with irony, the scene—set in McDonalds—elegantly addresses the political and social issues of race in addition to the beauty myth from which writer/director Nicole Holofcener’s heroines suffer.

• Mad Men Greg Kihn was ahead of time singing about the retro suits who “can buy New York with [a] plastic card”:

“Well, I get up every morning about 7 o’clock, catch the 9:02 and I make several stops. I keep the conversation and my pattern light, I hit the elevator, oh I feel alright. I check the numbers first and I’m right on time, I watch the traffic jam in a perfect line. Oh the city may burn but I keep my cool, on the best of days I think of school. I’m a Madison Avenue Man, I can make your fantasies part of my plan. I’m a Madison Avenue Man, well let me touch your money with my Madison hands, alright.” Madison Avenue Man

• Mad Men: Shut the Door. Have a Seat.

” . . . he knocked at the president’s door at Bascome and Barlow’s advertising agency.

‘Come in!’

Armory entered unsteadily. ‘Morning, Mr. Barlow.’

Mr. Barlow brought his glasses to the inspection and set his mouth slightly ajar that he might better listen.

‘Well, Mr. Blaine. We haven’t seen you for several days.’

‘No,’ said Armory. ‘I’m quitting. . . .I don’t like it here.’

‘I’m sorry. . . . You seemed to be a hard worker — a little inclined perhaps to write fancy copy —

‘I just got tired of it,’ interrupted Amory rudely. ‘It didn’t matter a damn to me whether Harebell’s flour was any better than anyone else’s. In fact, I never ate any of it.—This Side of Paradise-F. Scott Fitzgerald

• Mad Men Season Four Fall Out Three

• Marie Antoinette The girl in the curl.

• Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World Technically well done, but it’s no Captain Ron.

• Matchstick Men Is there anything wrong with an obsessive-compulsive disorder? Not when it puts the quirk in the con artist.

• Melinda and Melinda A cast of comedians with distinct voices of their own, yet Woody Allen’s odd harmonics still resound:

Josh Brolin (jumping on a trampoline): What do you do for exercise?

Will Ferrel: Tiddlywinks. And an occasional anxiety attack.

• The Method Fest You know when Martin Landau arrives in beautiful downtown Burbank to attend your film festival—you’re firmly pinned on the indiefest map. The Holiday Inn, the “official hotel” of The Method Fest is also the site of Frank T.J. Mackey’s infamous “Seduce and Destroy” seminar in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia. Talk about method acting.

• Milk Hope floats.

• Minority Report Tom Cruise falls into The Gap. Steven Spielberg does his utmost not to fall into his usual sentimentality trap. The total recall of long-ago plot twists (Witness, The Fugitive), however, mars its futuristic sheen.

• Mission Impossible III Shift into Cruise control.

• Monsters, Inc. The exhilarating swinging door ride is what Disneyland’s Space Mountain might look like if you blast off with the lights on. The Monster’s Inc. trailer promoting Harry Potter — sheer marketing magic.

• MTV Movie Awards 2002 Theme: “Movies Kick Ass.” They do. And so do co-presenters Jack Black and Buffy.

• MTV’s The Hills Laguna Beach Orange crush navel gaze.

• MTV Jersey Shore “These are not my people”.— John Joseph Cappa, 100% Italian American (aka The Boon) “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery” — as illustrated by Michael Cera’s swelled-head gelled-head imitation photographed between Snookie and Sweetheart. Youth in Revolt!

• MTV2 School of Surf Malibu High School vs. Ocean City, New Jersey

Write Between the Lines: Were you ever aware of the cameras?

Skylar Lawson: “I was always aware because they were always in my face.”

• No Country for Old Men There will be blood.

• Nowhere in Africa An elegant evening gown serves as both contentious point of bitterness and savior of sanity for an exiled German Jew family in 1930s Kenya. Internal marital conflict set against the backdrop of WWII — on the vast plains of Africa — is yet another filmic realization of history’s necessary lessons.

• NYC Prep

PC: I want to get out of The City ’cause I’ve been here for 18 years . . . just meet a whole new crowd. Not be in the same bubble, with the same people and the same reputation . . .start fresh . . . I don’t know, the more I think about L.A., the more I dread it.

Kat: You realize you’re not going to do any work, you’re going to do the same things, you’re going to have the same drama, it’s absolutely inevitable.

• The OC We’ll miss those crazy kids’ antics, especially the boy banter:

Seth: I think I made the worst mistake of my entire life. Now I need to get Summer back and I have to get into Brown.

Ryan: Great. How?

Seth: That’s where you come in.

Ryan: We need a plan.

Seth: It’s going to be a long night, Ryan. A lot of whining, a lot of pining . . . Plan A: I fake my own death. You never want to underestimate the power of the sympathy vote.

Ryan: Is there a Plan B?

Seth: Yeah, yeah, I could hack in through the Brown firewall, into the admissions office mainframe, and reverse my acceptance.

Ryan: That’s actually good. You know how to do that?

Seth: I had an uncle who went to DeVry.

• Ocean’s Eleven Steve Soderbergh’s boys will be boys’ night out caper. Dapper Dan and neon glam.

• The Office BBC America broadcasts the pathos and bathos of office politics — without a bloody laugh track.

• The Office Of course we love the UK version, and we do ask for helpings of Extras, but take particular delight in the U.S. Office‘ shout-outs to other great TV shows: To wit:

Pam: “Movie Mondays” started with training videos. But we went through those pretty fast. Then we watched the medical video. Since then, it’s been half hour installments of various movies, with the exception of an episode of Entourage, which Michael made us watch six times.

• The Office: Cocktails

Dwight: Do you watch Battlestar Galactica?

Party Guest: No.

Dwight: No? Then you’re an idiot.

• Pan’s Labyrinth “Do you believe in magic, in a young girl’s heart?” Guillermo Del Toro’s masterful mix of historical fiction and fantasy results in a fabulous fabula.

• Personal Velocity and Women on the Edge of a Nervous Breakdown engage us with risqué and at-risk women and their tame-to-tragic tales. Both end with unborn babies who have a personal velocity of their own that will not be denied.

• The Pianist Adrien Brody survives the ravages of WWII in the streets and hiding places of Warsaw, and reveals with complexity the systematic progression of freedom lost when the sheer survival of his body, mind, and music becomes paramount.

• Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End True, there are underdeveloped storylines, overboard swashbuckling scenes, yet . . . Being Johnny Depp hallucinogens, knave Keith Richards guitar strums, the fey the feints the quirks and the quips call for a rousing round of Yo Ho Yo Ho a Pirates life for me.

• Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl A bit of Shakespeare, silent film, vaudeville, with many asides to a complicit audience. Depp at his most inventive; Rush stole his voice from Hannibal Lechter. All ages may safely enjoy this ride.

• Quantum of Solace Save the story, save the world. Despite the fierce pierce of Bond’s gimlet eyes, the film cannot be Bourne. Casino Royale is a much better bet.

• The Queen Helen Mirren may play the pristine Queen of England, but in real life she’s the girl in The Gap.

• The Quiet American A slow-moving, intoxicating look at love in Vietnam, and the American CIA’s backing of a third-party in the early 1950s—culminating in more than two decades of the U.S.’s involvement in the country. Michael Caine displays his usual brilliance. Brendan Fraser as the CIA operative; how does he get such juicy roles?

Editor’s Note: The Quiet American is based upon the Graham Greene novel of the same name.

• Rabbit-Proof Fence A beautiful film—handled with unusual cultural sensitivity. Kenneth Branagh is his superb self, playing an insensitive civil servant (who genuinely thinks he’s civilized and sensitive), the rest of the cast, for the most part, are Aboriginal young people with no prior acting experience. The result, filmed against an arresting Australian background, is a stunning triumph of the human spirit. The rabbit proof fence is a metaphor for the walls that separate the Aboriginal people from the white invaders of their ancestral land. Another example of colonial imperialism gone awry.

• Rachel Getting Married The cure for this melancholic, albeit fine film? Dr. Drew’s Celebrity Rehab.

• The Real Housewives of Atlanta Mercy! You are cordially invited to this Aunt Pitty Pat party. Smelling salts optional.

• The Real Housewives of Atlanta Peach s(ch)nap(p)s.

• The Real Housewives of New Jersey — Season 2

“Counting the cars

On the New Jersey Turnpike

They’ve all come

To look for America.”— Simon & Garfunkel

• The Real Housewives of New York City Proving there is no difference between apples and oranges.

• The Real Housewives of New York City — Season 3

“You don’t wear chiffon on Christmas Day.” Gloria metes out wedding dress etiquette.

• The Real Housewives of Orange County White trash with cash.

• The Real Housewives of Orange County: No Boundaries

Gretchen: Are we brawling? Where do we live? Are we in Jersey?

• Real Woman Have Curves If you had to watch America Ferrera without dialogue, her facial expressions and body language would give all you need to know. Realistic and a fresh look at feminism. There is no man bashing, and everybody wins, even Mamá, who, it appears at first, doesn’t, but in the not-too-distant-future, will. A clash of cultures and generations where all come out with their dignity and self-worth intact. A terrific soundtrack as well.

• Reality Television is no longer a guilty pleasure. All of us who watch are just plain guilty. Leave it to The Simpsons to point out the error of our ways. In “Helter Shelter,” Homer and the family agree to reenact the 1800s time period for the “Reality Channel”:

Network Woman: The show’s getting boring. We’re losing viewers.

Network Man: I have an idea. It’s crazy, but it just might work. Like it did last week, on another show. We bring in the biggest, most famous star from a 70s sitcom whose phone hasn’t been disconnected.

Cut to Marge opening the front door:

Marge: Squiggy?

When Laverne and Shirley’s Squiggy fails to increase ratings, extreme measures are taken:

Network Man: All right, this still isn’t working. Fixing this show is going to take some original thinking. Everybody pull out your TV remotes and start flipping around.

The episode closes with the title Joe Millionaire spelled out in dollar bills—and Homer popping them in his mouth.

Homer: Mmmm . . . promo . . .

• Reaper: Charged

Sock: You’ve finally found the one thing you’re good at. You sent an escaped soul back to hell and you kicked ass. We kicked ass.

Sam: I’m good at stuff. OK? Other stuff. Right?

Sock: Ah, you do rock the house on Guitar Hero.

Sam: That’s what I’m talking about.

Kevin Smith fingerprints, Ray Wise pearly whites, & home store slacker boys brew tease and sympathy for the devil.

• Rocket Science Rapid fiery Anna Kendrick (New Moon’s bright star) foils Hal Hefner in this story filled with pluck and rue. We’re Spellbound in Jeffrey Blitz’ Garden State.

• Running With Scissors . . . and dancing as fast as I can.

• Tweaked Out: The Salton Sea Val Kilmer, sporting a faux-hawk and a big tattoo of the titular eerie landscape, portrays a meth addict, a snitch, a jazz musician or all three in this wannabe Tarantino meets Trainspotting po-mo mess. It poses the question: Who is this man and why is he so tortured? My answer: Who cares?

• School of Rock I know, it’s only rock ‘n roll — but I like it, like it, yes I do. Get yer hey ya-ya’s out in pedagogues Richard Linklater, Mike White, and manic Jack Black’s music appreciation class.

• Scrubs: My Chopped Liver . . . Speaking of TV’s love for TV . . .

TV Announcer in background: Stay tuned for more Gilmore Girls.

Turk: Mothers and daughters. They speak so fast, but they speak so true.

• Sex and the City: The Movie Much ado about/ hairdos fashion dos and shoes /Big girls soul mates true.

• Shopgirl We love gloves. As an aside, Frances Conroy appears to be the go-to mama for red-headed daughters. One exception, however, is Joan Allen, mother of Christopher Moltisanti’s fave D-Girl Alicia Witt in The Upside of Anger.

• Sidewalks of New York Brittany Murphy is the 2001 “It Girl.”

• The Simple Life: Mortuary Interns Nicole Richie (to clients): “We can arrange it, so you get washed with Irish Spring before you’re buried . . . since you’re Irish.” Did she pick up this excellent tip from her guest spot on Six Feet Under?

• Six Feet Under Death cab for cutie.

• Slither Slick sick flick.

• Slumdog Millionaire Luckily, the creators of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” did not pay attention to Newton N. Minow’s “Vast Wasteland” landmark speech, decrying TV (& particularly singling out game shows).

• The Sopranos Tower of power.

• The Soup Enlist in Joel McHale’s Navy. Splicing The Hills’ Spencer and Heidi’s horror show with The Hills Have Eyes 2 is reason enough.

• South Park Matt Stone and Trey Parker take no prisoners as they wield their mighty sword of a thousand truths, especially in episodes like Make Love not Warcraft.

• Spider-Man (A 2nd Opinion) Every time Tobey Maguire appeared, I kept waiting for him to pull out his Cider House Rules medical bag. He just could not sell me on the Clark Kent persona since he looks about ten years old, however, once the costume went on (and the body double stepped in) Spiderman came to life. About halfway through, when Macy Gray makes her cameo, you notice she is the only minority that stands out. From the stars down to the extras, diverse New York City is turned into Provo, Utah. The story is great, and the special effects are well done. George Lucas needs to take a look at this movie. Memo to George: fewer special effects, more story! By far the best part was the Green Goblin and psycho man Willem Dafoe. Every time he comes on screen you are instantly aware of just how good an actor he is. Like Nicholson’s Joker, Dafoe’s Green Goblin fits his personality well. You may have noticed I did not mention James Franco. My only hope is that he retires from acting before the sequel.—John J. Cappa

Editor’s Note: Commentary regarding Kristen [sic] Dunst in a wet tee-shirt and cheerleading movies “. . . this is where she excels” has been omitted due to the reviewer’s obvious unawareness of Ms. Dunst’s fine body of work, e.g., crazy/beautiful, Dick, E.R., and The Virgin Suicides, to name of few.

Additionally, the reviewer clearly was not an avid follower of Freaks and Geeks, in which James Franco did his best James Dean.

• Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron Executed with sweeping animation and minimal dialogue, Spirit is a rousing retelling of the settling of the old west, told from the point of view of a wild mustang whose spirit cannot be broken.

• Star Wars – Episode II: Attack of the Clones Blasphemy! I’m not a fan of the Star Wars series. This time out, however, I am impressed with ILM’s galactic extravaganza—the celestial cityscapes, the hallucinogenic-induced creatures, Amidala’s couture. The Anakin/Amidala love story? Loathsome. Hayden Christensen’s soul-deadening delivery of the cliché riddled dialogue? Excruciating.

• Starter for Ten James McAvoy plays a Bright Young Thing in this hip Brit 80s Quiz Show.

• Stick It and Bring it On Power puff grrrls.

• The Strangers

“Strangers in the night exchanging glances

Wond’ring in the night what were the chances

We’d be sharing love before the night was through?”

Chances are zilch in this chill summer horror flick filled with childlike singsong on vinyl, dollfaces masks, and helter skelter switches.

• Summer Heights High Why watch? Ikea: The Musical.Need we say more?

• Superbad Dazed and Confused Freaks and Geeks party on 70s style.

• Surf Girls Blue Crush, but with cheesecake and whine.

• Talk to Her Obsessive Love (El Amor Obsesivo), appears to be the theme of Pedro Almodovar’s Academy Award winning screenplay. Marco, a journalist, is obsessed by his ex-girlfriend, who was obsessed by drugs. Lydia, obsessed with being bullfighter, to upset her disapproving father. Benigo, a male nurse, first obsessed by mother, then by Alicia, the comatose girl in his care. Alicia, obsessed by ballet before her accident. Her ballet teacher, played by Geraldine Chaplin in a wonderful turn, obsessed by Alicia and by ballet. The director presents the viewers with a plateful of so-seemed misfits. In the end, however, each character has given something positive to Marco and Alicia, who, the audience is left to believe, will become obsessed with each other, in a healthy way. An interesting footnote: on a bedside table, a Spanish translation of The Hours.

• There Will Be Blood Double, double toil and trouble/Fire burn, and oil bubble.

• A polaroid of contributor Jesse Cole Crowder with the caption “‘SEEMS DIFFERENT’ since Feb. 2003” can be seen in the opening credits of the 2004 sci-fi film They Are Among Us. Ah, the things we do for our film school friends.

• Transformers Motormouth Shia LaBeouf is a fun Hasbro action figure — the only bright shiny toy is this 144-minute-long advert.

• Roll of Tropic Thunder, hear my cry. Tears of laughter.

• True Love Lovers smote by monsters in the shape of a precocious thirteen-year-old playwright or a made in Japan Godzilla cannot extinguish the true love in Atonement and Cloverfield. Stories told in novel and camcorder form, both heartthrobs are named Robert. Coincidence? Not in J.J. Abrams Lost world.

• Unhook the Stars What to watch on Mother’s Day with the woman who gave you life. Writer (with Helen Caldwell)/director Nick Cassavetes creates a lovely thank you for his lovely mother, Gena Rowlands.

• The United States of Whatever Paul McCartney protégé and Tenacious D best friend Liam Lynch’s musical flash of brilliance. Punk rock phenomenal.

• Wall • E Remember the Spike Jonze’ commercial for Ikea, “The Lamp?” The media is the mixed message.

• Whale Rider Winner of Audience Award: San Francisco, Sundance, and Toronto. A 12-year-old Maori girl in New Zealand struggles to change her grandfather’s patriarchal mindset. Through Paikea ‘Pai’ Apirana’s single-minded persistence and an astonishing ocean journey, she eventually convinces Koro that she is as equally capable as a male to head up their tribe — and that sometimes, certain traditions and cultural ways need to make way for the new. This is an optimistic, mystical, and spiritually uplifting tale the audience really wants to believe in, and therefore wholeheartedly does.

• The Wedding Banquet The following missive courtesy of acerbic attorney Dennis Wong:

Katy:

Michelle and I watched Ang Lee’s Wedding Banquet last night and were pleasantly entertained, however, we both agreed the screenplay is rather pedestrian. It merely chronicles everyday Chinese life. The story is particularly uneventful when compared to the drama and deceit that occurs at the Wong family on a daily basis. As a result, I would like you to visit my 98-year-old grandmother or my parents for the magic “four” days and evaluate whether my family is worthy of a screenplay or, at minimum, a sitcom. I really don’t want to extend myself if the end result is not marketable.

Thanks,

Dennis

• William McKinley The Go -To school for Glee and the E.L. Konigsburg classic, Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth.

• The Wrestler Who has his own action figure bobbling by the dashboard light? Mickey Rourke, that’s who.

• You, Me and Dupree — The Break-Up Funny girls Kate & Jen act more as fashion plates than soul mates in boys’ club members’ Matt + Owen & Vince + Jon’s romantic comedies.

• YouTube Why join? OMG! To try on the “Shoes.” — random review by Irish laddies MacGuinness and Killian.

Editor’s note: Or, go straight to another nice Irish lad’s website, Liam Kyle Sullivan’s a liam show. Betch.

Y Tu Mamá También The caddish charmers have a manifesto that includes such statements as: “Truth is cool but unattainable.” Ceci, the cool unattainable woman they wish to seduce, has one as well: “You’re not allowed to contradict me.” Ceci rules!

• The Rachel Zoe Project We die.

“She is not happy, unless everyone around her is panicked, nauseous, or suicidal.” — The Devil Wears Prada

Ashton: . . . We’re in Atlanta.

Brad: Have you run into any of the housewives of Atlanta? Like Nene or Kim?

Rachel: Brad’s a little obsessed with Nene.

Ashton: I understand. Demi’s obsessed as well.

• The Rachel Zoe Project — Season 2

“I can’t think of anything worse than showing up at an event in a suit that somebody else is wearing. It’s exactly like that episode of 90120 when Brenda and Kelly wore the same dress to their prom.”—Brad metes out prom dress etiquette.

• Zoolander Ben Stiller puts the moue in model Derek Zoolander. Owen Wilson’s too sexy for his smirk . . .

Last but not least . . .

Awards Season Understatements:

Lucy: Let’s face it, Ethel. You don’t win an Academy Award by patting poodles on the head and crowning queens.

by Leigh Godfrey

Okay, first off, I don’t know anything about surfing. Never done it, don’t care about it, and until about three years ago, I wouldn’t even swim in the ocean (related to a traumatic experience seeing the movie Jaws when I was seven years old, but that’s another story). So right off the bat, I have to tell you that the reason I love the movie North Shore has nothing to do with the surfing. So as long as we’ve got that out of the way, we can get started.

North Shore follows the tried and true formula (which, incidentally, I appreciate very much) of the underdog overcoming all odds to reach his goal, and perhaps learning a little something along the way. In North Shore, our hapless protagonist visits Hawaii, learns to surf and falls in love with a local girl, thereby wreaking havoc on the tried and true ways of the Island. But, think less like Romeo and Juliet—more like The Karate Kid.

But with waves.

Given that North Shore has a story by Randal Kleiser, who brought us The Blue Lagoon with a script co-written by Tim McCanlies, who is responsible for The Iron Giant, you can only guess what kind of a movie you’re getting yourself into.

Our story opens and I, for one, am immediately sucked in by the hot action shots of dudes surfing radical waves to the tune of a Pseudo Echo song. Our hero Rick Kane (Matt Adler) is one of these surfers, and lo and behold! he wins the big surf contest. That’s right, a groovy silver belt buckle and five hundred bucks. When asked what he’s going to do with his $500 prize, Rick shouts out: “I’m going to Hawaii to surf the big waves of the North Shore!” This of course seems like an excellent plan until we realize the contest Rick has won took place in a wave tank in Arizona! But you’ve got to love his ambition.

After a quick confab with his mom, we realize that Rick is not only going to Hawaii with just $500, no real surfing experience, and not knowing a soul, but he’s also forgoing his dream of becoming a graphic designer. Now, name me another movie where the main character is a graphic designer AND a surfer. Go on, I dare you.

Naïve Rick alights in Honolulu and a few extraneous things happen obviously inserted into the film to show the various sides of life in Hawaii. Briefly, Rick gets into a cab and asks to be taken to an address that was given to him by some drifter that stopped by the wave tank one day. Rick seems to think this guy will give him a place to stay. So we see him cruising the main drag of Waikiki, where neon lights and prostitutes abound. The address turns out to be a strip bar—the Hubba Hubba Room. First, Rick is hit on by a hooker who wants him to buy her a $20 glass of champagne, next, he’s dissed by his “friend,” and last, gets himself into a bar brawl.

Hawaii sure ain’t like Arizona, Rick is thinking.

This leads to Rick jumping into a Jeep with two randy Australian surfers who were at the strip club. They turn out to be professional surfers Alex Rogers (played by Robbie Page) and Mark Occhillipo (that’s “Occy” to you). For no apparent reason, these two immediately take Rick through a burning sugar cane field and make him jump out and pick some, until Rick is chased by some locals with machetes—perhaps to show the audience the truth about the Hawaiian sugar industry? Who knows? It really has no place in a surfing film, but then again, this is so much more than a surfing film.

Anyway, after all this, they end up back at a beach house heavily populated with hot babes, and it just so happens to be owned by surfing legend and Rick’s personal hero Lance Burkhart (portrayed by surf pro Laird Hamilton). This is where one of the many fine lines uttered in the film occurs: when Occy tells Alex to get into the hot tub with him, and Alex says (please put on broad Aussie accent): “Right, I love skin diving.” Classic. Just as an aside, these two surfers are obviously gay, but throughout the film they are constantly surrounded by babes, therefore taking away the subplot of big gay love that might have otherwise taken place.

The next morning, Rick goes out to catch his first big wave of the North Shore. The first sign this is a mistake is when Occy looks at Rick’s board (surfboard, that is) and says “Twinnies? No one rides twinnies here, mate.” A twinnie being a twin-finned surfboard. Rick says he’ll be okay, but poor Rick is clearly so dumb about surfing he doesn’t stand a chance. After all he doesn’t know how to “duck dive” and when he finally catches a wave it’s just “a ripple.” As Alex says: “Where’d you learn to surf, in a bathtub?” Then, Rick commits the cardinal sin of all sins; he pisses off the Hui (pronounced “hooey”). That’s right, Rick causes the Hui to wipeout and all hell breaks loose.

He returns to the beach to find “those guys in the black trunks” have stolen his stuff. Realizing they’ve hooked up with a loser, Alex and Occy quickly ditch Rick, and as he wanders aimlessly about with his board, he runs into a local surfer dude, which brings us to the main reason why I love the movie North Shore — Turtle.

Turtle, played by John Philbin with true surfer aplomb (he also starred in that other notorious surfing film, Point Break), is Rick’s entrée into the surfing world of the North Shore. It’s Turtle who informs Rick in no uncertain terms that those guys in the black trunks are the Hui, and the Hui are not to be trifled with. In fact, his exact words are: “They’re the Hui. Nobody messes with the Hui.”

Turtle is so endearing, even though he goes against everything I find attractive in a man, I can’t help but have a crush on him. He is also responsible for 90% of the great lines in this film, which, when I quote them here, must be imagined in a surfer dude accent, often ending in the word brah or a hang loose sign, or both. If you don’t know what that sounds like, please visit Scott’s North Shore Page where you can hear the actual lines themselves.

On their way to a happening Halloween party, Turtle begins to teach haole Rick a few important lessons about Hawaiian slang:

“What’s a haole?” asks Rick.

“It’s the local word for tourist,” explains Turtle.

Rick: “I’m not a tourist.”

Turtle: “Whatever, barney.”

Rick: “What’s a barney?”

Turtle: “It’s like barno, barnyard. A haole to the max. A kook, in and out of the water, yeah?”

Yeah. That sums up Rick. To the max.

Rick meets cute local girl Kiani at the party, but unfortunately she happens to be head Hui Vince Moaloaka’s cousin. So you know that’s going to be trouble. Since Rick doesn’t have a place to stay, he asks Turtle if he can crash at the shaping shack where Turtle works, sanding surfboards for the enigmatic Chandler, master board shaper and “soul surfer,” who is played by Gregory Harrison. Best known for his role as Dr. “Gonzo” Gates in the ’70s TV series Trapper John M.D., this is one of only a handful of films you’ll see Harrison in that aren’t movie-of-the week related.

Lance Burkhart shows up at the party looking like Rocky from the Rocky Horror Picture Show and demands Chandler have his surfboard ready by the next morning, so Turtle and Rick return to the shaping shack to sand Lance Burkhart’s board.

The next day, the waves are really cranking at Pipeline so Turtle and Rick hit the surf with disastrous results, even though Turtle had given Rick all the info he needed to know about surfing Pipeline: “There’s a reef that starts here and goes all the way down there. So when the wave breaks here, don’t be there . . . or you’re gonna get drilled.”

Rick, of course, bites it big time, breaks his board and scrapes up his back on the reef. Kiani comes riding up the beach at this inauspicious moment and exclaims: “You’ll get reef rash if you don’t put something on those cuts.”

If you’re unaware of the dangers of reef rash, rest assured that a little aloe will cure you.

At this point, everyone is pretty much embarrassed by Rick, and now that his surfboard is busted and the Hui stole all of his stuff, he hasn’t got a lot left. He goes back to the shaping shack with Turtle. Chandler walks in toting a set of drawing pencils, which he has just purchased at a pawnshop. Rick exclaims they are the ones stolen from him by the Hui, and proves it by showing Chandler a watercolor he did of a dude surfing the big waves of the North Shore. Chandler agrees to give Rick a place to stay and a job sweeping up the shaping shack in exchange for the painting, which he then gives to his wife. Awww.

After discovering Rick is pretty much a menace to surfing society, Chandler decides to teach him about the waves, so he can become a true “soul surfer.” Rick learns to surf in a brief montage set to some lame song that sounds not unlike that song played over the karate contest montage in The Karate Kid. I’d like to interject here, what is it about these 80s movies soundtracks? Any movie geared toward teenagers that was made in the 80s had the worst music. Obviously, the concept of licensing popular songs for soundtracks was not thought of back then, with John Hughes being the lone possible exception. And even he had a few major missteps (Belouis Some, anyone?).

Back to Rick’s learning to surf montage. It is intercut with scenes of Rick sketching various drafts for Chandler Surfboards’ new logo. Apparently, as his surfing improves, so do his design skills. After going through many incarnations, the logo ends up looking exactly like the painting Rick had given to Chandler in the first place, so I’m not quite sure why he went to all the trouble.

While Rick is learning to surf, this creepy guy with a floppy canvas hat takes a bunch of pictures of him and convinces Rick that he can be as successful as Lance Burkhart. Naturally, he’ll have to enter and do well in a big surf contest such as the conveniently located Pipeline Classic. In the meantime, Rick has managed to hitch a ride out to some remote part of the island where Kiani lives. While there he indulges in some Hawaiian activities. He attends a luau, watches Kiani hula dance and gets into a fight with the Hui who stole his stuff, thereby regaining his honor and his cool silver surfboarder belt buckle. Kiani and Rick have a little love scene on the beach, and head Hui Vince decides Rick isn’t such a bad haole after all.

At this point, you may be wondering (as am I) where the heck is Turtle? Well, poor Turtle is sanding away for Chandler, all the while nurturing his own ambitions to be a master shaper. He even has a “big gun” tucked away in a closet, that he’s made all by himself, but is too afraid to show to Chandler. And his bitter resentment of favorite son Rick is growing stronger:

Turtle: “I hear Chandler’s trying to teach you how to shape.”

(Rick nods)

Turtle (sullenly): “I’ve been his sander for five years, Chandler teach me how to shape? Not even. Chandler ask me home for dinner? Not. Coach me how to big wave surf? No way.”

Rick: “Look, maybe it’s because we have this design thing in common.”

Turtle (scoffing): “Yeah, right — design thing. Design me out of the picture, haole. Here on the North Shore we treat friends mo betta.”

Poor Turtle!

Back at the beach, Rick decides to enter the Pipeline Classic, much to the chagrin of mentor Chandler, who derisively exclaims: “Go ahead. Go shred.” (I once again ask you to recall The Karate Kid, and how Arnold from Happy Days was really upset that Ralph Macchio wanted to enter that karate contest to fight the guys from the Cobra Kai. It’s just like that.) See, Chandler’s 60s surfing sensibility doesn’t jibe with the 80s “hot-doggers” like the Lance Burkhart’s of the world. But Rick needs to find his balance (just like Ralph Macchio) so he first rectifies the situation between Turtle and Chandler by stealing Turtle’s surfboard and giving it to Chandler. Chandler is so impressed, he goes surfing with it and we get to see some of Gregory Harrison’s big moves. Creepy guy in floppy hat asks Turtle: “Who’s that?” And Turtle proudly replies, “Chandler. On my board. That I made.”

I often wondered why we never get to see Turtle surf. He only surfs once, in the beginning, then after that he is either sanding or on the beach. We do, however, get to see him without his shirt on, a lot, so I guess I have to be satisfied with that.

So Turtle, Chandler, and Kiani all come out to see Rick surf the big contest. The soul surfing pays off and he makes it all the way to the finals and has to surf against his former idol Lance Burkhart. They match each other wave for wave, but finally, a cheating Lance Burkhart steals Rick’s final wave and foils his chances of winning. It doesn’t matter though, because Rick now knows he can hold his own with the best. And of course, Lance gets his comeuppance, as creepy guy in floppy hat has taken photos of the whole thing and Lance is humiliated in the local press the very next day.

Which, incidentally, is the day that Rick says goodbye to Turtle, Chandler, Kiani, and the big waves of the North Shore to go to New York and pursue his dream of graphic art. Kiani tells Rick she prayed to the Kahunas that Rick would come back to the North Shore. But she’s no prophet, because the film didn’t do well enough for a sequel.

Alas.

Editor’s Note: There is, however, the punch drunk love of Boarding House: North Shore.

Author’s Note: Apparently, Turtle gives surfing lessons in Malibu. Guess where I’ll be this summer?

by Kem Kem

Mother and Nun Fun.

Nic Cage OZ Raggedy Ann.

Station Wagon Rides.

by Katharine Elizabeth Monahan Huntley

“Every garment worn in a theatrical production is a costume. Before an actor speaks, their wardrobe has already spoken for them. From the most obvious and flamboyant show clothing, to contemporary clothes using subtle design language, costume design plays an integral part in every television and film production. It is an ancient theatrical craft and the process today is identical to when Euripides was writing long ago. Costume design is a vital tool for storytelling.”—The Costume Designers Guild

Eilish floats out of her boudoir, tanned and trim in a skin-tight white leotard and gauzy skirt. “It’s my schlep around thing. All pieces of taffeta, embroidered by hand. It zips into a miniskirt.”

Of course it does. It’s the exact sort of garb Aaron Spelling’s chic costume designer would wear to lounge around the manor. With an Irish lilt, she offers: “Tea, or perhaps a mimosa?” Followed by: “I have miniature lemon muffins baking in the oven.”

Charmed, I’m sure.

Irish Eilish

One of nine children, Eilish McNulty, an Irish Catholic living in Belfast, Ireland, was taught in St. Catherine’s Convent by Dominican Nuns. She excelled in the domestic arts.

Eilish: I would make my own clothes. I designed my first dress when I was nine years old. Turquoise with white dots the size of quarters. Polka dots. A peter pan collar with short sleeves and a full gathered skirt with two big patch pockets. As a teenager I would buy fabric Saturday morning for the dress to wear to the dance that evening. This may surprise you, but to this day, Ireland is ahead of U.S. fashion by at least six months. Great fashion comes out of Europe.

Eilish, nominated for two Emmys for Murder She Wrote, prepares to costume Angela Lansbury for the actor’s latest project—in Ireland. Any notion of Eilish “lounging around” while on hiatus from cult fave Charmed is pure fabrication.

Eilish in Camelot

“Film is the great collaborative art. The design triumvirate—the director of cinematography, the production designer, and the costume designer—struggle to create an invented world to help the director tell their story. A film is one gigantic jigsaw puzzle. A movie is an enormous architectural endeavor of sets and lighting and costumes for one time and one purpose. This minutely crafted kingdom must sit lightly on the shoulders of the narrative.”—CDG

Eilish immigrated to the United States at the age of twenty. After a short stint as a governess in Toluca Lake, and a whirlwind romance with Tony Zebrasky whom she married (very Aaron Spelling), she became a seamstress for Warner Bros. Eilish began sewing in the tailor shop, and soon thereafter was promoted to the finishing end of the costuming department, which led to—

Eilish: My first film was Camelot.

Under John Truscott’s extravagant and artistic direction, Camelot went on to win the 1967 Academy Award for Best Costume Design. Eilish went on to collaborate with glamour gurus Bob Mackie and Nolan Miller. She’s dressed glamour girls from the vintage beauties: Ann Baxter, Elizabeth Taylor, Lana Turner, Miss Bette Davis, to young Hollywood: Shannen Doherty, Holly Marie Combs, Alyssa Milano, Rose McGowan. Perhaps it is Eilish’s Celtic heritage that has fated the costume designer to hone her craft on shows about angels (Charlie’s Angels), vampires (The Kindred), and witches (Charmed).

Eilish: I started working for Aaron Spelling in 79 or 80. Charlie’s Angels, Love Boat, Vega$, Hart to Hart, Hotel . . . . The 80s were big shoulder pads and men’s pantsuits. Street kids with colored hair, cutting off tee shirts and ripping them up. I worked on Dynasty for ten years. Joan Collins, high fashion, and hats. At one point I was overseeing seven shows.

WBTL: I’m an unabashed fan of Spellingvision. I’ll never forget the pilot episode of Dynasty. Fallon (Pamela Sue Martin) biting the wedding cake bride’s head right off. I was instantly hooked.

Eilish: Television is different from real life. Aaron’s shows are exciting, contemporary.

And, whereas Spelling television is camp, Eilish is class. Read: Eilish doesn’t dish. Alas.

Charming Eilish

“When a costume designer receives a script, the process of developing the visual shorthand for each character begins. Costume sketches, fashion research and actual garments are used to help costume designers, directors, and actors develop a common language for the development of each character. Sometimes a glamorous entrance may be inappropriate and destructive to a scene. The costume designer must first serve the story and the director.”—CDG

Eilish affectionately refers to the Halliwell sisters—Phoebe, Piper, and Paige, as “my girls.” Phoebe (Alyssa Milano) is clearly her favorite. I imagine Eilish as a kind of Mary Poppins amongst the mischievous vixens.

Eilish: My girls have a unique look; there is a new wardrobe for every performance. I take into account the shade of their eyes, hair tint, and skin tone. Although the cast is color coordinated, I’m careful the actors are never in the same color at the same time. Nor do they have the same neckline.

“The more specific and articulate a costume is, the more effective it will be with an audience. Minute details loved by actors often enhance their performances in imperceptible ways. Many actors credit their costume as a guide to the discovery of their characters. Actors sometimes need sensitive costume design for imperfect bodies. Flattering figures, camouflaging flaws, and enhancing inadequacies are part of the job description.”—CDG

WBTL: Is there undo emphasis on the body beautiful?

Eilish: Their bodies need to be a slim shape. That’s what they’re paid for.

WBTL: Do you dress the actor or character?

Eilish: A bit of both. For a guest star, I definitely dress the character. For the girls, it’s best to dress them in clothes in which they’re more comfortable. Holly likes solids, Alyssa—carefree and could care less, Rose’s signature color is red. Rose wouldn’t wear in her personal life what she wears on the show. Not for a minute.

Stylish Eilish

“Costumes have always had enormous influence on world fashion. When a star captures the public’s imagination, a film or television role has catapulted him or her there. A style cycle begins as this role is recreated in retail fashion to the delight and demand of fans. The exposure this celebrity brings to a costume generates millions of dollars for the fashion business. When a film engages the public’s psyche, it is a powerful selling tool for a clothing manufacturer. Costume designers receive tremendous pride from seeing their efforts reproduced on a global scale, but little recognition and no remuneration for setting worldwide trends.”—CDG

WBTL: How do you keep fashion in fashion?

Eilish: I buy garments up to six weeks ahead. That’s really the window of time.

WBTL: Where do you shop for Charmed?

Eilish: Fred Segal on Melrose. Bleu has fabulous clothes. Yellow Dog. Traffic. Little boutiques carry eclectic styles. The Saks 6th floor is super trendy. The dilemma with the boutique designers is, once I’ve decided on one outfit—I need to purchase five of the same because of the stunts! Two for Alyssa and three for the stunt girls. My budget is high-end—$20,0000 a week. The outfits are expensive, but you do get what you pay for. The fit has to be great; they have to walk right into their clothes.

WBTL: Action figures!

Eilish: I outfitted Alyssa in black pencil pants with an overskirt, so she could do her kicks. Then we saw everyone putting skirts over pants—jeans with a chiffon skirt.

WBTL: What do you like to wear?

Eilish: A lot of black. White. A little pink, a little red. I organize my closet according to color. No floral prints.

WBTL: Fashion tips?

Eilish: Just because they’re showing hot pinks, oranges, and reds, it doesn’t mean you should wear it. Dress in colors that make you feel good, feel at ease. A smart woman dresses for herself, doesn’t try to be the latest thing. Black never goes out of fashion. The little black dress never ever goes out of fashion. Hiphugger jeans—very few women can get away with them. Of paramount importance are shoes! Shoes make or break the outfit. My friend Nolan Miller insists a full-length mirror is essential, and I concur. Study your body. Say to yourself: How do I look? How do I feel?

Luck of the Eilish

“Costume designers are passionate storytellers, historians, social commentators, humorists, psychologists, trendsetters and magicians who can conjure glamour and codify icons. Costume designers are project managers who have to juggle ever-decreasing wardrobe budgets and battle the economic realities of film [and television] production. Costume designers are artists with pen and paper, form, fabric and the human figure.”—CDG

WBTL: Have you ever thought of designing a personal line?

Eilish: I’ve been so fortunate with my career—it’s kept me much too busy to consider my own line. And the money is incredible.

WBTL: Career versus family conundrum?

Eilish: Every Friday night when my son Mark was a little boy, I would leave the Warner Brothers’ lot and stop off at a toy store. One evening I was too late. The store was closed. And I walked into the house and Mark asked: Where’s my present? . . . [sigh] . . . . He would play baseball, and teetering in my high heels I would be sneaking into the bleachers from the back so he couldn’t see I was late . . . . If you juggle being the perfect wife, mother, friend, and career woman—you often end up feeling like a failure. But I’ve been blessed with a husband who fully supports my choices. If I were delayed, he would take over the household when I couldn’t be there—giving Mark dinner, his bath. Even now, I come home from the set Tony has dinner on the table—the wine is poured . . .

I glance around Eilish’s spacious home as we exchange farewells. The elegant white-washed dining room where she and Tony sip their spirits opens out to a glittering view of the San Fernando Valley. She then packs me off, warm muffins in hand. Gracious Eilish. Leads a charmed life.

When Irish Eyes are Smiling

Mark Zebrasky, the adored only child of Eilish and Tony, was known as “Mr. Z” at Saint Robert Bellarmine where he taught 2nd grade. A snappy dresser (and occasional Charmed extra), he was a great favorite among all the children, and in particular, of two Irish laddies, MacGuinness and Killian Monahan Huntley.

Work Cited

“What is Costume Design?” The Costume Designers Guild, 2002. www.costumedesignersguild.com

Postscript: Click the Fred Segal image to read: “Hollywood Ending.”

by Katharine E. Monahan Huntley

C. Houston Sams is from Texas (San Antonio) — but she is no relation to famous fellow Texan Sam Houston. The “C” stands for Charlene. As is in Dallas’s Charlene Tilton. Although both blonde, there is no confusing J.R. Ewing’s baby sister’s baby doll persona with the prep school punk rock fashion plate whose cool client list ranged from the commercial to the cult. Celebrities (Quentin Tarantino, Tracy Lords), musicians (Tenacious D, Midget Handjob), and magazines Spin, Nylon, Blender, Premiere, Hollywood Life, Bikini Ray Gun . . .

When did you first become interested in fashion?

Houston: At thirteen I took my first trip to Dallas. It was there I came across a vintage boutique. I thought, “How cool are these clothes.” It was 1980, and I didn’t care for contemporary trends — I liked the 50s styles. Vintage opened up a new world for me. I started making stuff. Sewing and creating. The dilemma was — I didn’t have anywhere to wear my new wardrobe.

Fast forward 8 years. Houston and her retro wardrobe go to Hollywood.

Houston: I started taking classes at UCLA and with that, raking up debt. That got old fast. I had to get a real job. I had nothing to wear for interviews but my 50s and 60s apparel. I answered an ad in the Recycler: “Actress needs assistant.” I put on my “Marilyn Suit” — a baby blue fitted three quarter length sleeve jacket and a pencil skirt. Platinum blonde bobbed hair. As fate would have it, the actress was this redheaded woman, Susan Bernard, the daughter of Bruno Bernard: “Bernard of Hollywood.” He was the glamour photographer for, among others, Sophia Loren, Jayne Mansfield, and, of course, Marilyn Monroe.

WBTL: You were in costume for the job.

Houston: Her son is Joshua Miller, one of kids in Rivers Edge.

Rivers Edge, a seminal independent film, is almost as terrifying as Joshua Miller’s father Jason Miller’s film, The Exorcist, in which he plays Father Damien Karras.

Houston: I would help Susan market the photos. Read the “Breakdown” for Joshua, a daily paraphrased list of auditions for roles agents are preparing to cast. You can identify what character types they are looking for and choose what roles might work for a particular actor. All the major talent agencies get it. . . . Around Halloween I was telling Joshua about my costume: a she-devil on wheels. I explained, ‘You know—like Russ Meyers’ films?’ He exclaimed, “What? Mom was in the Russ Meyers’ Faster Pussycat Kill Kill.”

“A cornerstone of both camp and punk cultures —no mean feat — Faster Pussycat Kill! Kill! (1966) shows the thrillingly lethal consequences when aggravated go-go dancers get bored. Russ Meyer’s black-and-white desert Gothic melodrama — for some viewers the crown jewel in a flashy career . . .” (Morris, Bright Lights Film Journal).

Houston: She came to my party in Hollywood, and all my friends were asking for her autograph. After working with her for a year and a half, I was inspired by the images . . . I needed to go do that — take photos and learn more of the technical aspects of my trade. Including plain old sewing.

After all this I met a girl at a party and she was wearing the coolest thing. She was a costume designer. I asked her about it, and she introduced me to Louise Mingenbach (The Usual Suspects, X-Men, X2, Starsky & Hutch). Up until that point, movies had never occurred to me . . .

The fashion fabulist will eventually return with the entire story, including tales of how working with Melanie Griffiths is not Another Day in Paradise — but how working From Dusk Till Dawn with Roberto Rodriguez is, anecdotes about Judith Frankland, Dogtown and Z-boys, The Gettys, Pleasant Gheman, and just what exactly it is a wardrobe stylist does.